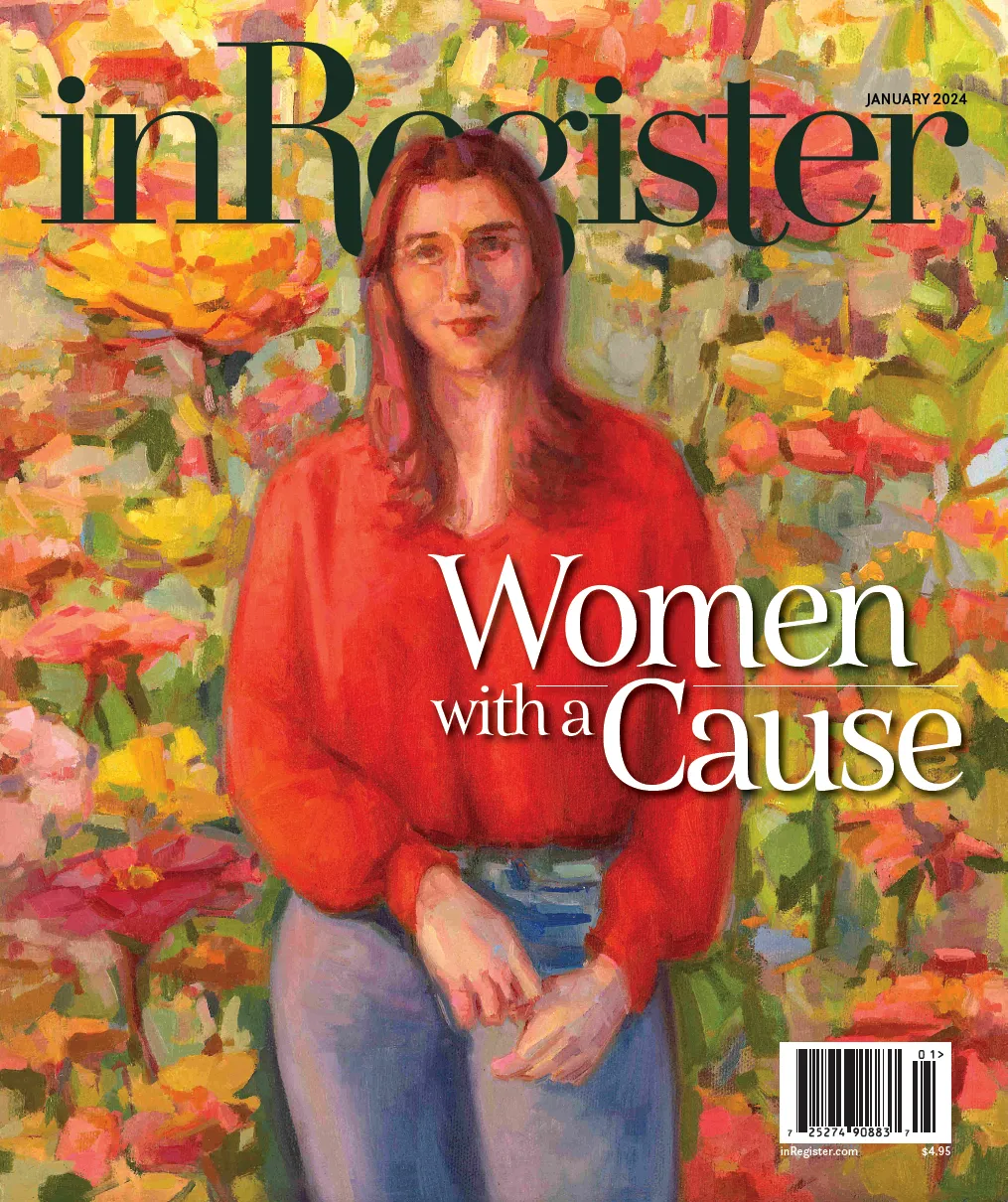

The legacy of A. Hays Town lives on through his loved ones’ memories and mementos

Whenever Leslie Hays Gladney wasn’t on the school bus home, her mother had a hunch where she might be.

Sure enough, the child would turn up later with her beloved grandfather, A. Hays Town.

Town would often walk from his Third Street office to scoop her up from St. James Episcopal Day School. She’d join him on jaunts on his private plane to Lafayette or Jackson, Mississippi. She’d shadow him on jobs and client visits. They’d forage for porcelain, brick and brass in New Orleans. They’d investigate buildings, noting the intricacies of a transom or a gate, the layout of a courtyard and the way the colors of the sky reflected in a window. They’d paint and draw together.

“He was an explorer,” Gladney recalls. “I think my sense of curiosity came from him.”

Each adventure sparked a new lesson—and one of the region’s most storied architects happened to be Gladney’s teacher.

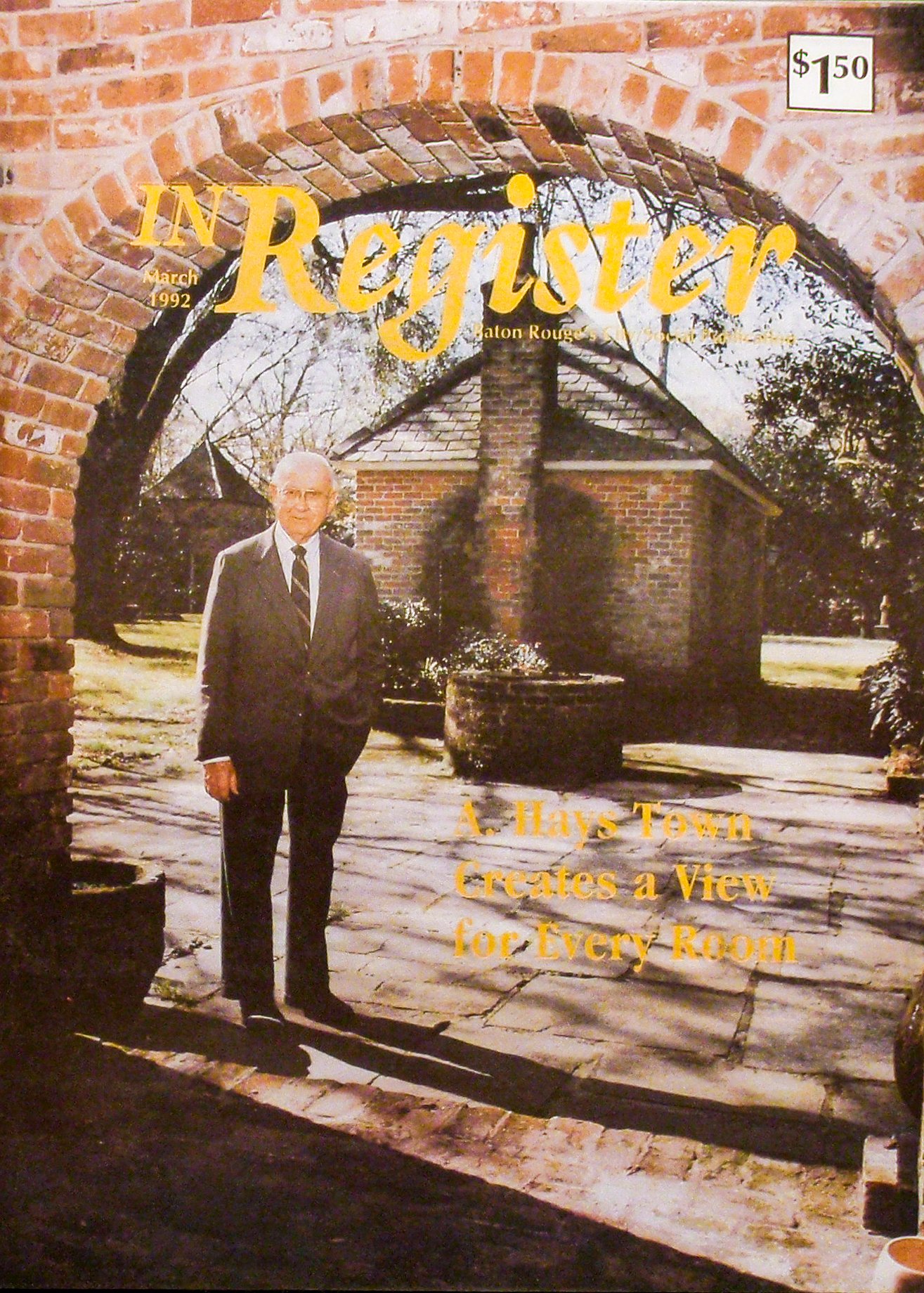

Before his death in 2005 at age 101, Town built more than 1,000 houses, churches, schools and other buildings. He had an outsize influence on architecture in Baton Rouge, where he’s known for popularizing features like soaring 13-foot ceilings, beeswax-coated brick floors and floor-to-ceiling windows designed to frame outdoor vistas. His trademark full-length shutters and deep, covered porches didn’t just lend character; they provided thoughtful solutions to life in south Louisiana’s harsh climate.

The release of Town’s 1985 book, The Architectural Style of A. Hays Town, forever changed local construction, according to architect Kevin Harris.

“So many builders started capturing little fragments and details from his book, putting them into their spec houses and improving the style and the livability of the neighborhoods,” says Harris, principal of Kevin Harris Architect and president of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art’s College of Chapters.

Town was always experimenting. He’d study the alchemy of paint colors, how a single drop of green or blue hue could chemically alter the whole mood of a room.

Gladney, who grew up to be an artist and a real estate agent, fondly remembers his trailblazing, no-rules spirit from their day trips.

“He never minded going where you weren’t supposed to go, like down a dirt path,” she says.

He wasn’t afraid to cross metaphorical dirt paths, either. He’s widely heralded as one of the first architects to recycle materials. Long before today’s vintage-adoring, sustainability-minded generation, he was salvaging old beams, bricks, mantels and doors.

He wasn’t afraid to cross metaphorical dirt paths, either. He’s widely heralded as one of the first architects to recycle materials. Long before today’s vintage-adoring, sustainability-minded generation, he was salvaging old beams, bricks, mantels and doors.

“Now everybody wants to do it,” Town told inRegister in 1992, referring to the era’s growing trend of upcycling. “I lived at the right time. These things won’t be possible in the next century.”

He also helped pioneer wheelchair accessibility, Harris says. He believed wide doorways and halls were safer for aging families, children, pets and those with disabilities.

Town was famous for fostering familial relationships with his clients. After a project concluded, he continued to advise them on art, furnishings or even what breed of dog might best complement their space.

It’s with those homeowners in mind that Gladney will notify a listing agent if a property is falsely marketed as an A. Hays Town house.

“Not because someone would misuse his name or profit off of him,” she explains, “but because it could hurt his families he did build for. He wanted to protect them.”

Harris is currently working to restore one of Town’s houses, scavenging for original paint colors preserved behind electric panels.

The project has him thinking back to the ’80s when he asked Town for his thoughts about using expansion joints in plaster to prevent cracks.

Plaster is supposed to crack over time, Town insisted. It’s just as lovely as the wrinkles that develop on aging skin.

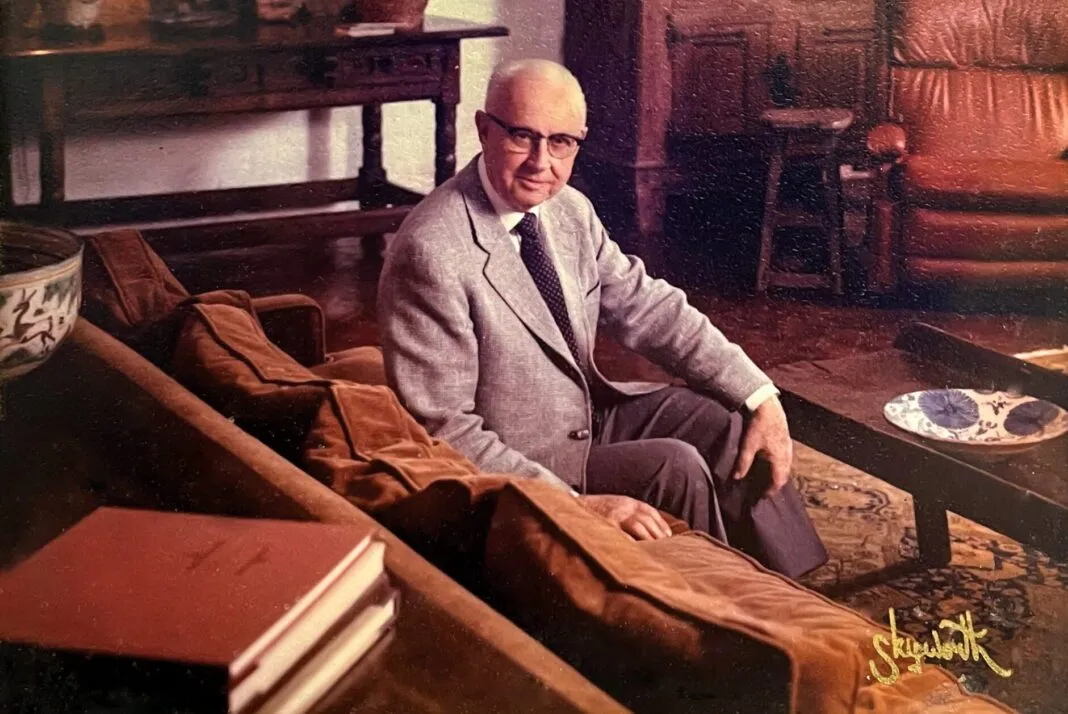

In her dining room today, Gladney spreads a collection of leather photo albums across the table. She pauses to talk about a family portrait or a picture of Town’s own immaculate Stanford Avenue property.

The pages of the album are weathered, some of them sticking together. But just like cracking plaster, the memories inside these worn photographs—and her grandfather’s own legacy—have only gotten lovelier with time.