On solid ground: Furniture craftsman Ford Thomas

Each morning, woodworker Ford Thomas rises before the sun and drives 30 miles into Baton Rouge from his home in East Feliciana Parish, three dogs in tow, arriving at his century-old building on Laurel Street by 8 a.m. He throws his weight into heaving open the massive metal sliding barn doors original to the building, a style so old it’s new again, and lets Ogee, Izzy and Blue trot in.

The 12,000-square-foot, industrial-style warehouse has been home to Thomas’ company Benchworks Custom Handmade Furniture for the past 14 of his 38 years as a professional woodworker. He has gained local notoriety for his work in dozens of churches and spiritual spaces across Louisiana and even out of state, crafting bulk orders of chairs and pews—a wondrous accomplishment for an operation of his size. Over the years, his smaller product line of picture frames, clocks, small shelves and cutting boards have had fantastic success at trade shows around the country, being picked up by retailers like Neiman Marcus, The Nature Company and Williams-Sonoma.

While there is no doubt that Thomas’ pieces are works of art, when he speaks of his process, he sounds like less of a designer and more of a gear-head, an engineer. For him, the process is brass tacks, the “nitty gritty of how we’re going to make it.” He draws his designs to scale on graph paper, incorporating clean lines and multiple colors and species of wood in nearly every piece. “I use dark wood as an accent, and a combination of others to achieve a look, to achieve the ultimate goal of a design,” Thomas says.

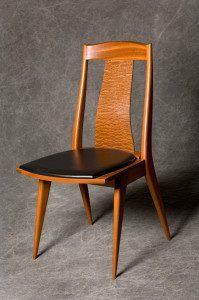

Years ago, Thomas was lucky enough to participate in a workshop with the late great American woodworker Sam Maloof, who is esteemed for his chair designs. Day after day, we sit in chairs—at desks, at breakfast tables, in waiting rooms, rarely questioning the humble chair’s ability to support our weight, never celebrating it for serving its simple purpose. But in the woodworking world, could there be any other piece of furniture with greater responsibility? They are time consuming to make, and a good chair can run nearly $1,000. Most woodworkers shy away from making them for the liability alone. But not Thomas. “It was a result of my meeting Sam Maloof and seeing his commitment to quality and design. That’s what got me started in making chairs,” Thomas says.

The key elements are comfort and ergonomics, the tilt from front to back that governs the comfort of a chair, he explains. The weak spot is the joint where the seat meets the back leg. “I started with that joint. In my chairs, that joint has to be as strong as possible,” he says, tilting backward in the chair to prove his point. So much goes into engineering the perfect chair that even after nearly four decades in the business, Thomas has just two basic versions that are timeless and incorporate the Maloof style of deep, dished-out seat. “I have a design that I can guarantee,” he says. “It isn’t going to fail.” His two versions are different in comfort and style, and he can change the back and front legs or the color to match a client’s needs.

Nowadays, professional and self-taught woodworkers need not look far to learn, with HGTV, YouTube and a slew of other information sources at the ready. But back in the 1970s, Thomas says, there weren’t a lot of contemporary American woodworkers, a genre he puts himself in. His main source of information was Fine Woodworking, a monthly magazine still in publication. “It was kind of a way for woodworkers to connect, to see who was doing what,” Thomas recalls. “Woodworking was kind of evolving and unique” back then, and the magazine featured tips on how to improvise in the workshop. “I used to wait for it to come in, then read it cover to cover,” he says.

Like all professions, technology and information has drastically changed the woodworking business. Still, not much has changed in the way Thomas does his work. “I’m comfortable with my methods,” he says. “I’ve tried to stick with the basics. Technology hasn’t really evolved me.”