The winners of the inaugural A. Hays Town Awards follow in the legendary architect’s footsteps

The projects that represent the inaugural winners of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art Louisiana Chapter’s inaugural A. Hays Town Awards are dotted throughout Louisiana and the broader South. They are homes. They are gardens. They are churches. They are concepts. They represent ideas, inspirations and, most importantly, the desire to preserve the architectural traditions of the past by bringing them into the present, just as A. Hays Town did during his decades-long career designing homes and buildings throughout the South.

Some of the nine winners knew Town during his life, whether friends or passing acquaintances, and some had barely been born. Either way, though, the influence of Town on these architects and designers is apparent even in subtleties.

“It feels like we are not only honoring his legacy but carrying it forward,” notes Atlanta-based architect Terry Pylant, part of the Historical Concepts design team who are recipients of one of this year’s awards. “A. Hays Town was one of the first people to actually use recycled materials in his homes, which is something we have done for years but he was the pioneer. His work carried important regional traditions forward so that we can do the same.”

Below, you will get a glimpse into each of the winning projects. From a 10-acre garden in Natchitoches to a church restoration in Albany, Louisiana, to a pied-à-terre in the French Quarter, each of the projects represents countless hours spent in pursuit of not only a beautiful result, but one that protects and preserves the architectural history of the South.

While A. Hays Town’s main focus was on the architecture of the home itself, his design vision didn’t stop at the front door. Given his inspiration was Louisiana and the traditional way of life of its people, it only makes sense that the exterior of the home would be just as important as the interior.

In this design by CARBO Landscape Architecture for a home in Shreveport, the goal was to create something that speaks to traditional Louisiana landscaping but in an updated way. Details such as a sugar kettle-inspired fountain made from concrete rather than cast iron and a steel skeleton pigeonnier showcase this old-meets-new approach.

“Referencing traditional English, French and Creole gardens, the landscape reflects the intertwined cultures that make up Louisiana, in a contemporary way,” notes landscape architect Michael Percy. “I would say there is a misconception that preserving history means copying it. Be inspired by classical design but make it your own.”

When approaching the addition and renovation of this church, built in Albany, Louisiana, in 1912, the Hoffpauir Studio team turned to the history of the structure, as well as its needs within the modern context, which included things like accessible seating and restrooms.

“The church was constructed by its parishioners, with many of the materials donated by the owners of a local sawmill,” explains architect Joshua Hoffpauir. “Historical accounts describe the construction taking longer than expected because most of the construction crew were strawberry farmers by day and church builders on weekends.”

Things like pine floors from the same time period were sourced. And, according to Hoffpauir, that’s what makes this renovation so special. “Because of our current culture, it is our nature to expect decisions and construction to be completed quickly,” he says. “But we must be willing to learn from and respond to the history of the place.”

For a Lake Charles new build, the goal of the Atlanta-based Historical Concepts Architecture & Planning team was to create something that felt like it had been there for years. Informed heavily by A. Hays Town, especially given the homeowners had worked with Town himself on a previous home, the result is a 6,000-square-foot home that stands as a reflection of the homeowners’ love of Louisiana and their—along with the architects’—desire to protect and preserve the building traditions of the South.

“Traditional architecture is grounded in a place and is informed by what came before it,” explains architect Camden McClelland. “Starting with those ideas leads to places with character and vibrancy that people want to be a part of.”

While Bill Brockschmidt and Courtney Coleman started their business in New York City in 2001, they moved their operations down to New Orleans in 2019. With architecture backgrounds and a dedication to classical interior design, their two winning projects—one in a carriage house in the French Quarter and one a small home in Greenville, Mississippi—represent their love of the South and their dedication to creating interiors that speak not only the client, but the history and culture of the area in which a home is located.

“We want the spaces to feel of their place,” Coleman notes. “For that reason, all of our inspiration comes from where they are.”

In the New Orleans project, vibrant shades of gold, pink and green were utilized to speak to Creole influences, as well as the exuberant nature of the French Quarter. In the Mississippi project, the emphasis was on creating an elevated, lived-in feel. Cotton fabrics were sourced to make the new pieces feel collected, and shelves and other surfaces were filled with keepsakes, artworks and more that were special to the owner.

“Classical principles can be applied in so many ways that aren’t just elaborate moldings,” Brockschmidt explains. “Color, proportion and even things like wallpaper borders can all be informed by the classical style.”

Baton Rouge-based architect Kevin Harris, who also serves as the current president of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art Louisiana Chapter, looked outside of Louisiana for his award-winning project. His design for a Dominican convent in Dallas brings together a multitude of influences to achieve a structure that is functional and feels of its place, hinting at the history of both Texas and the order of Dominican sisters.

“The convent was designed as a memory project to celebrate the origins of the Dominican order in Rome, the Dominican mother house in Nashville, and the origins of the introduction of Christianity to Texas through the Spanish missions,” Harris explains. “The plan was arranged in a crucifix pattern with four wings inspired by the apse of Santa Sabina and three Texas missions. All of the decorations in the chapel were taken from the frescoes of these missions, and each of the doors, windows and ornamentations help tell these stories.”

“This project was a labor of love,” landscape architect Jeff Carbo explains of this homestead in Natchitoches. “It was really a career-defining project for me.”

Originally a cotton field, the 10-acre property wasn’t new to its owners, having been in their family for generations, but the home they were building with the help of Al Jones Architects was.

“When they came to us, they told us the gardens were more important to them than the house,” he recalls. “That’s not the attitude that most people take, and it was special to be able to work with a client who is a good steward and is fully committed.”

The idea was to create something that looked like it had been there 100 years, keying into the grand details of traditional Louisiana landscapes with details like a circle of aged live oak trees. And it wasn’t done overnight, as the project took eight years to reach its full realization.

“With landscapes, it’s not like a brick wall,” Carbo explains. “It’s always growing and changing, and for that reason, our work is never truly done.”

In addition to established architects and designers, the A. Hays Town Awards also spotlights up-and-coming professionals. One such professional is Samuel Methvin, who won for the latticed pergola he both designed and built himself in Shreveport.

“As the sole designer and builder of this project, it has been an opportunity for me to apply the knowledge and skills I have been eagerly developing since my interest in classical architecture began at an early age,” he explains. “The pergola sits on the property of a historic home built in the 1920s located in Shreveport, Louisiana. Various structures already exist on the site, so I incorporated several elements from them into my design to maintain and reinforce the harmony and continuity that already exists.”

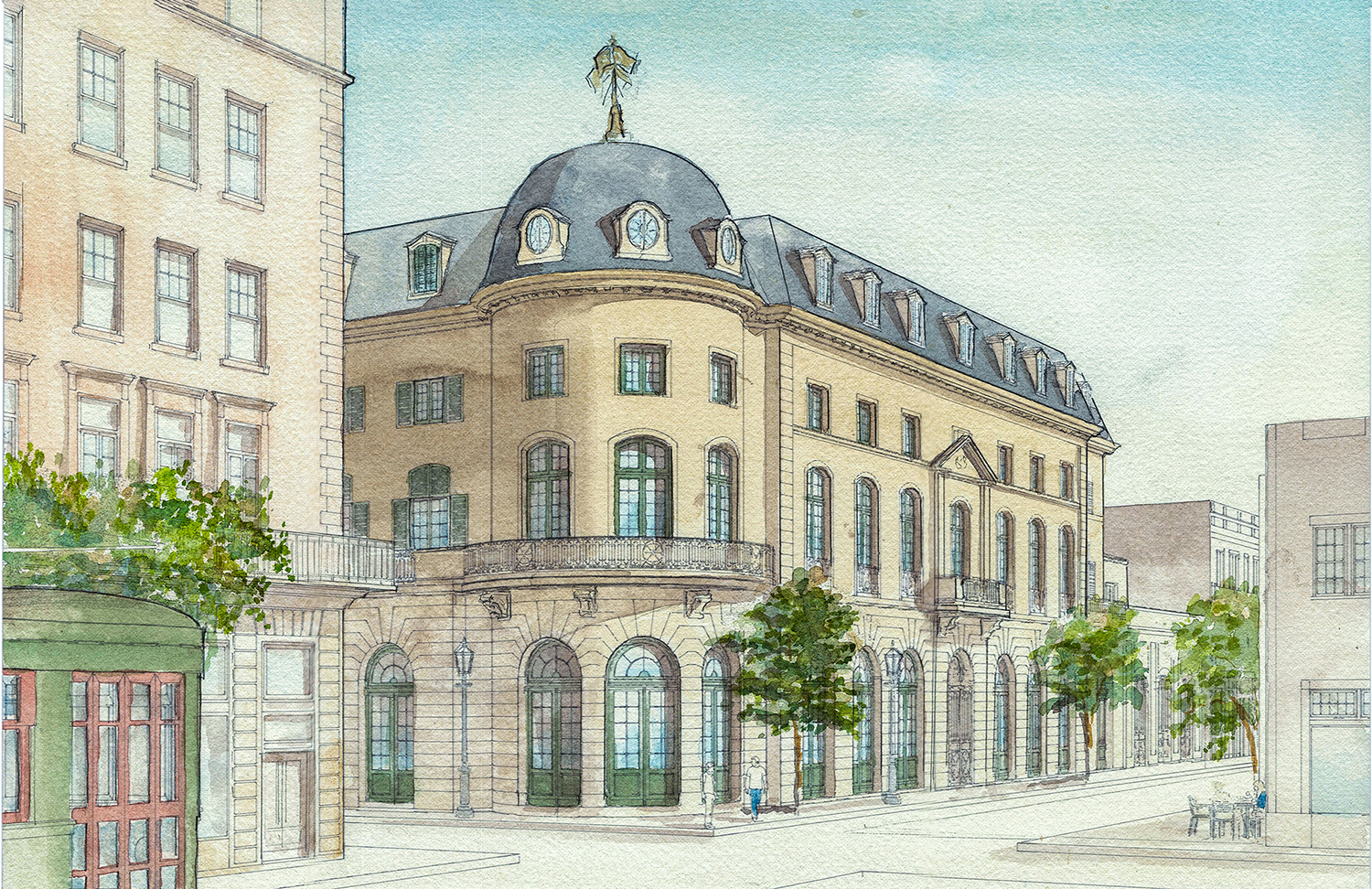

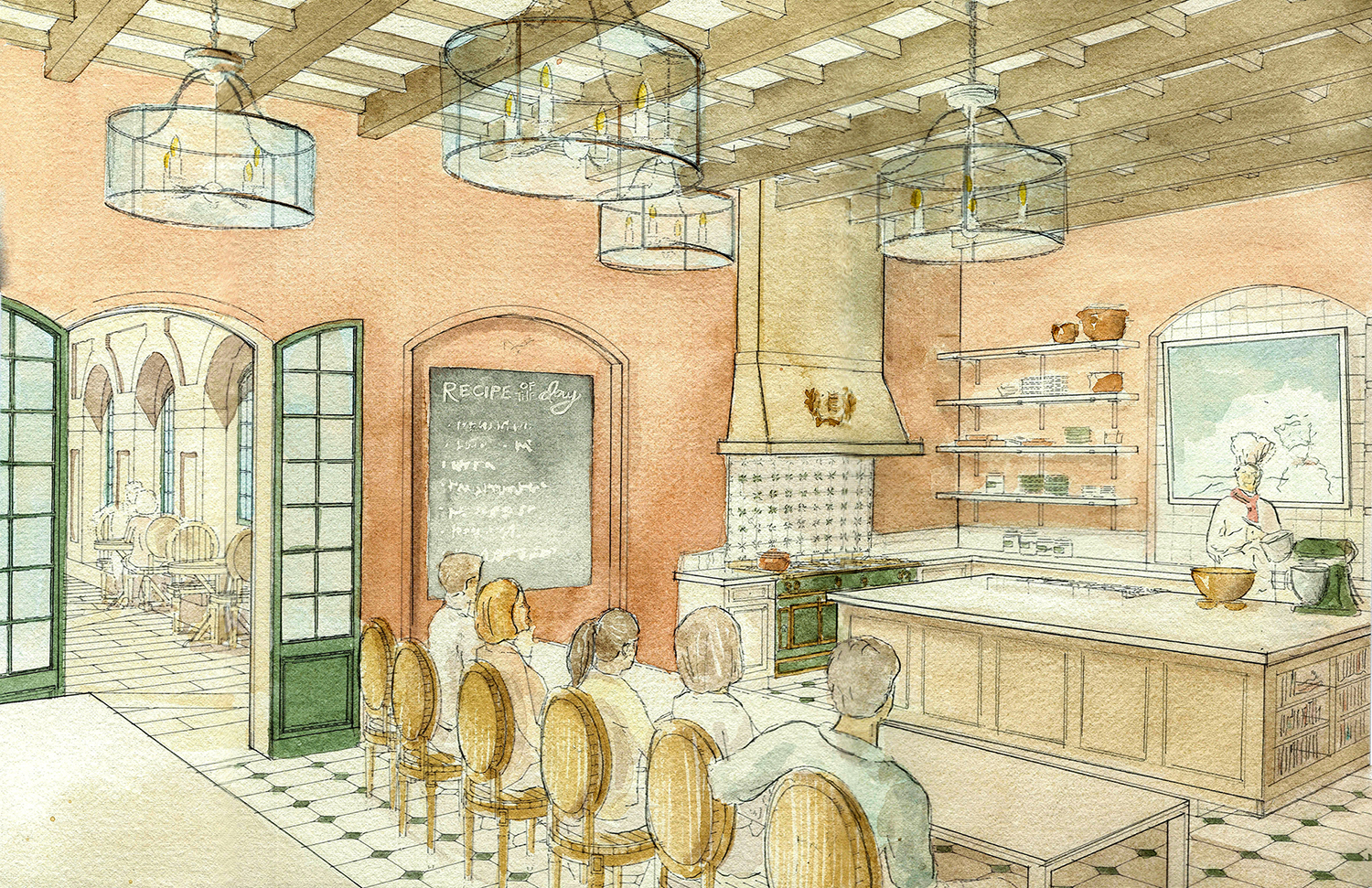

Another young winner, Elizabeth Woodard Petagna’s design for a culinary school in the Central Business District of New Orleans draws upon the French, Spanish and Creole architectural influences that are present throughout the Crescent City. The very idea to design a culinary school, though, is something that was informed by Petagna’s growing up on the Northshore and observing the importance of food to Louisiana culture and life.

“I grew up an hour away from this remarkable city that inspired my love of traditional architecture,” she explains. “The elements gleaned from study of the local vernacular and historic influences allow for a building that feels familiar, local and appropriate to New Orleans.”

Considering everything from event space for Mardi Gras balls to trolley access, every aspect of Petagna’s design points to her love for New Orleans and her desire to create even more opportunities for the community to engage with one another and the unique culture of the place.