Silent treatment: Pelvic floor therapy

Pelvic floor physical therapists suggest ongoing exercise to all of their patients.

An embarrassing physical matter benefits from significant therapy now available

Social media is inundated with people oversharing about their health issues. Open up Facebook to view photos of severe wounds, minute-by-minute updates on cosmetic surgery, and explicit details about infections. One would think that, these days, no personal detail is too private for the masses. However, there are many who are suffering in silence. When it comes to bladder dysfunction or pelvic pain, many women and men are hesitant to bring up the topic—even in the privacy of their doctors’ offices.

“Pelvic floor dysfunction is an umbrella diagnosis that includes organ prolapse, incontinence, sexual dysfunction and some types of constipation, among others,” explains Ochsner OB-GYN Evelyn B. Griffin.

The source of all of these problems is weakness, spasm or constriction of the pelvic floor muscles. And because the pelvic floor muscles affect many bowel and bladder functions, it’s not uncommon for patients to have more than one problem.

A relatively small number of men experience pelvic floor problems, and those issues are likely to result from complications following prostatectomy, colon cancer surgery or chronic prostatitis due to muscle weakness.

Griffin estimates 20% to 40% of women will suffer from a pelvic floor problem at some point in their lives. Peak Performance Pelvic Floor Clinic therapist and clinical director Lacie Barbier reports 90% of patients are women.

But many are just too embarrassed to talk.

“Statistics show it takes 9 years on average for a woman to say something to her doctor about having incontinence,” she says. “That’s crazy because women typically see their doctors regularly, get gynecological exams and are not shy about getting treatment for other conditions.”

But it shouldn’t be that embarrassing. It’s actually a loss of estrogen rather than a loss of control that prompts the onset of most incontinence and many pelvic muscle problems. The pelvic floor is like a hammock surrounding the urethra, the vaginal area and the rectum. The structure helps to hold urine, stool and even some organs in place.

“When women go through menopause, their muscle strength starts to weaken,” says Barbier. “That’s when some people experience incontinence for the first time.” Earlier in life, hysterectomy or difficult vaginal deliveries may cause problems to develop as well.

Even though the onset may begin with pregnancy or menopause, women do not have to accept these symptoms as part of life, when effective therapy is available and affordable.

The first step in seeking treatment is a visit to the primary care physician, who may run tests, prescribe medication and refer the patient to a urologist, urogynecologist, gynecologist, gastroenterologist or other specialist, or directly to physical therapy.

When a woman comes in with symptoms, Griffin begins with a history, physical exam and appropriate tests. “Often the diagnostics are negative, so the patient has no idea of what to do next,” she says.

Once a gynecological problem is ruled out and Griffin believes the pelvic pain is musculoskeletal, she typically suggests physical therapy.

“It’s a bridge to get back to normal,” she explains. “What they learn in therapy can benefit them in the long run. These problems tend to be chronic. So patients need to learn to live with the condition, and then they can improve.”

Whether the problem has persisted for 20 years or results from a recent surgery or pregnancy, an estimated 80% of physical therapy patients experience substantial improvement in less than a month. Unlike most medication, treatment has no negative side effects and may allow patients to get off medicines prescribed for the problem. Therapy is covered by most insurance plans, Medicaid and Medicare.

At Baton Rouge General’s Pelvic Health Rehabilitation Clinic, “We start with a physical therapy assessment that includes a whole body evaluation with posture, breathing and range of motion,” says physical therapist Kali Aucoin. “We do an extensive history that looks at back, hip and pelvic floor symptoms using physical exam and technology.”

From there, therapists develop a customized exercise program, which may incorporate manual therapy, behavior modification, postural correction, dry needling and weights—but not just any weights. “Some people think it’s kind of creepy, but we have a weighted baby,” she explains. “We want to be able to replicate real life, so a mom can learn the correct technique and posture while lifting the baby, just like at home.”

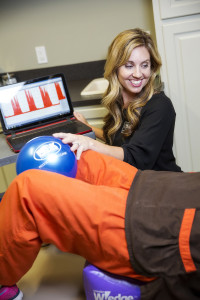

At Peak’s Pelvic Floor Clinic, Barbier specializes in core strengthening and pelvic muscle endurance, strength and coordination. While other treatments are employed, the cornerstone of her program is biofeedback therapy and electrical stimulation, which gives patients immediate feedback on whether the exercises are done correctly.

“I do believe [success requires] 50% muscle strengthening and 50% education [regarding diet, lifestyle, posture, etc.],” says Barbier. “Sometimes we get ourselves in horrible habits, and we just need some bowel and bladder muscle retraining.”

Therapy typically lasts 2 to 8 weeks—less time than to rehab an orthopedic injury. Because the success of pelvic floor therapy is related to reconditioning or retraining a muscle, a home exercise regime is important to maintain wellness.

Therapists know bowel and bladder treatment may never debut as a topic of polite dinner table conversation. However, patients are sharing their successes with family and friends.

“In the course of therapy, patients will frequently say, ‘My friend is having a baby soon, should she look into this?’ Or ‘My husband is constipated. Do you think this could help him?’” Aucoin reports. “So we encourage patients to become advocates.”

The Baton Rouge General program now has a waiting list; at Peak, Barbier schedules an average of 50 patients per week.

“I have patients who don’t leave their house,” Barbier explains. “They’re worried about leaking or not being able to find a bathroom. It’s so embarrassing.”

And to make matters worse, a patient’s symptoms increase when they become anxious or nervous because their muscles tense up. It’s a cycle.

“But then they go through the course of therapy and become social again. That’s huge. It’s life changing for the patients,” Barbier says. “That’s really why I do it.”