On Exhibit: AWA’s “Audubon Inspired”

Two hundred years ago, a newly fortuneless taxidermist with a penchant for portraiture set foot in New Orleans in hopes of beginning a new, hairbrained art project inspired by the wildlife of the vast United States—but first he needed the funds. They would come by way of Lucretia Pirrie, mistress of St. Francisville’s Oakley Plantation, who offered him a tutoring position for her daughter in exchange for room, board and the freedom to paint the area’s feathered, chirping residents to his heart’s content. The result? A catapult into the career-making art book The Birds of North America, whose success transformed John James Audubon into one of the most recognizable artists in American history.

This month, the Associated Women in the Arts honors Audubon’s legacy in Louisiana with its annual exhibition hosted at the Old State Capitol, this year titled “Audubon Inspired.” Consisting of 44 pieces made with various media depicting the architecture, wildlife and culture of our state, the artists aim to follow through with Audubon’s original desire to bring the beauty of the American natural world to the international stage.

“America was still a new country in his day, and states like Louisiana had only recently become a part of the nation,” says curator Lauren Davis. “There was so much to discover, and he had such a pioneering spirit.”

Of course, no perspective of Audubon’s influence would be complete without proper acknowledgment of the history that helped make his contemporary impact possible. “Several of the birds he depicted have since become extinct in part due to over-hunting, a practice Audubon promoted,” says Davis. “He also often relied on the expertise of local indigenous or enslaved African Americans to help him find species, but never acknowledged their assistance or skill. He was a slave owner himself.”

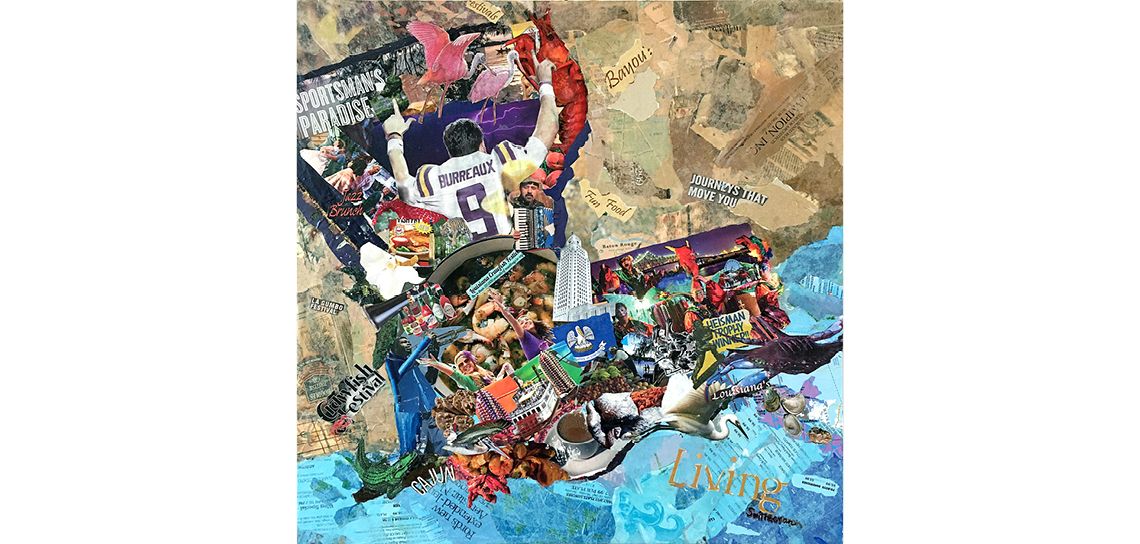

The exhibition, then, moves beyond that troubled past, with some of Davis’ favorite pieces—like Nancy Smitherman’s “Louisiana Bounty” collage, featuring a smorgasbord of cultural iconography, or Jane Chapman’s “Evening Fades,” a more traditional, impressionistic painting celebrating the untouched beauty of nature—displaying the joviality and, as she says, “the mystery of Louisiana that Audubon was probably drawn to when he first came here.”

On May 8, viewers can even join in on an urban version of Audubon’s preliminary scouting missions by taking part in a downtown bird walk in partnership with the Louisiana Ornithological Society, where—who knows?—the next great naturalist may find her inspiration.