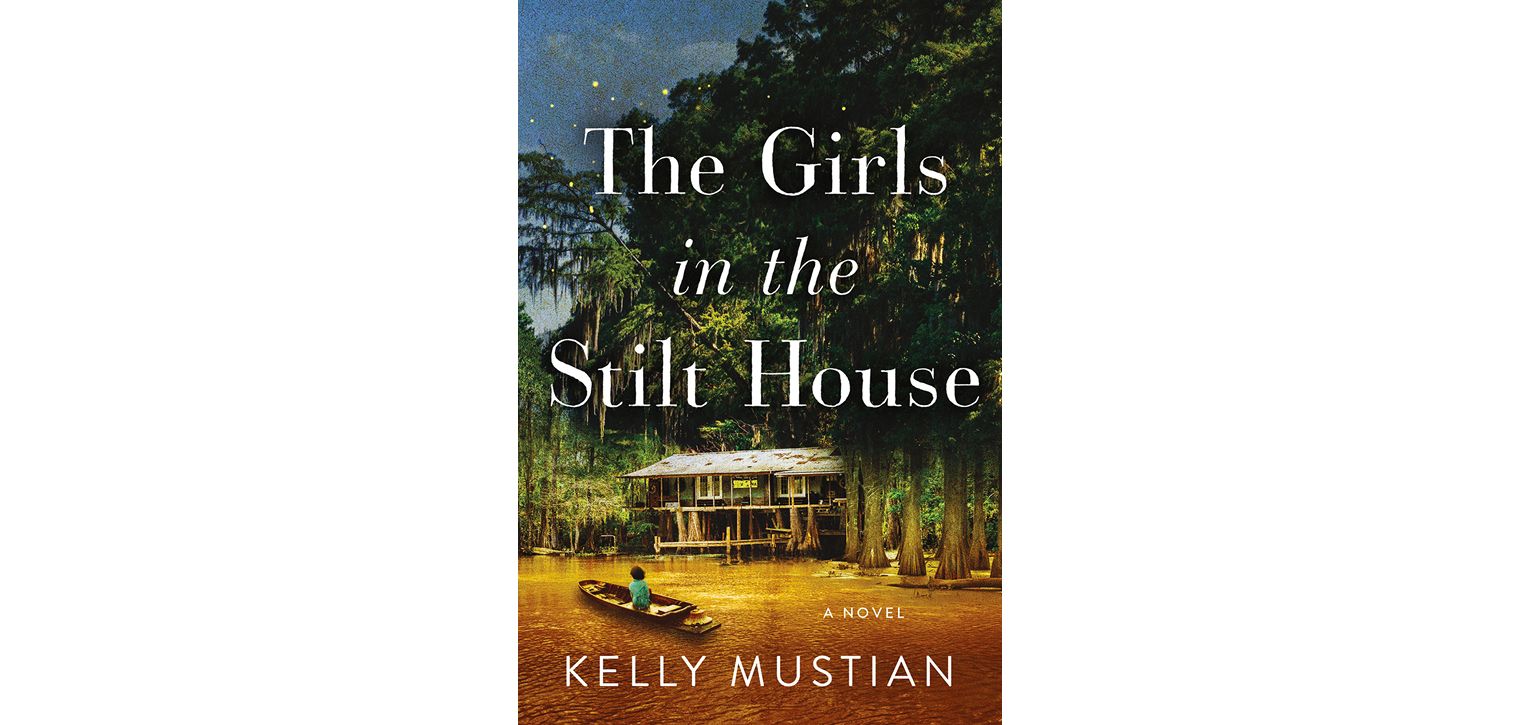

Off the Page: ‘The Girls in the Stilt House’

‘Let’s forget about everybody you used to know a little … It’s just you and me right now. That’s the way it’s got to be.”

When 16-year-old Ada Morgan hears these words in the spring of 1923, she merely nods, awestruck. It’s what happens when you accidentally engage in a murder with a mysterious 17-year-old runaway as your only attestant and accessory—and you a runaway yourself, still grieving a mother’s death and stinging from a boyfriend’s broken promises above a Baton Rouge barbershop. Now Ada and Matilda Patterson are stranded back home near the Natchez Trace in Mississippi, in a landscape haunted by Confederate headstones and lifetimes of poverty and pain. One the daughter of a white trapper and the other of a Black sharecropper, they have no choice but to trust one another to craft a cover story and keep a secret—and that’s just in the first few chapters.

In Kelly Mustian’s debut novel, The Girls in the Stilt House, the racial and economic tensions of the 1920s South stem from a history still visible today. The story is inspired by the Mississippi native’s own childhood among old Natchez storefronts and arrowhead-laden creeks. With her motley crew of midwives, bootleggers, writers and even a burgeoning archaeologist, Mustian narrates sticky summers and stickier morals of the urban-rural borderlands in an omniscient, character-hopping style part Lifetime serial, part Yoknapatawpha County drama. A necessary choice, perhaps, to balance the heightened complexities of everyday dreams and disasters. Ada wants independence but is thwarted by ignorance; Matilda wants to move north but is thwarted by lost opportunity. And a country that should be climbing the rungs of economic prosperity instead inspires a hidden relay of smuggling and crime.

Even so, the novel is no indictment. Not on its two headstrong protagonists, anyway, whose fraught friendship manages to maintain its threads through trauma and transformation, absence and additions. No matter which way the narrative leaps, Mustian’s love for her childhood home remains tender and true, caught up in its complexities like a bird in the canebrake, and proving that these old Southern haunts still have stories left to tell.