Off the page: ‘The Blues’

Since the debated decade of its creation, blues as a musical genre has built a reputation on its notorious fluidity—not just in the way its notes jaunt and jive across a page, but in the way its origin story changes hands depending on who does the telling.

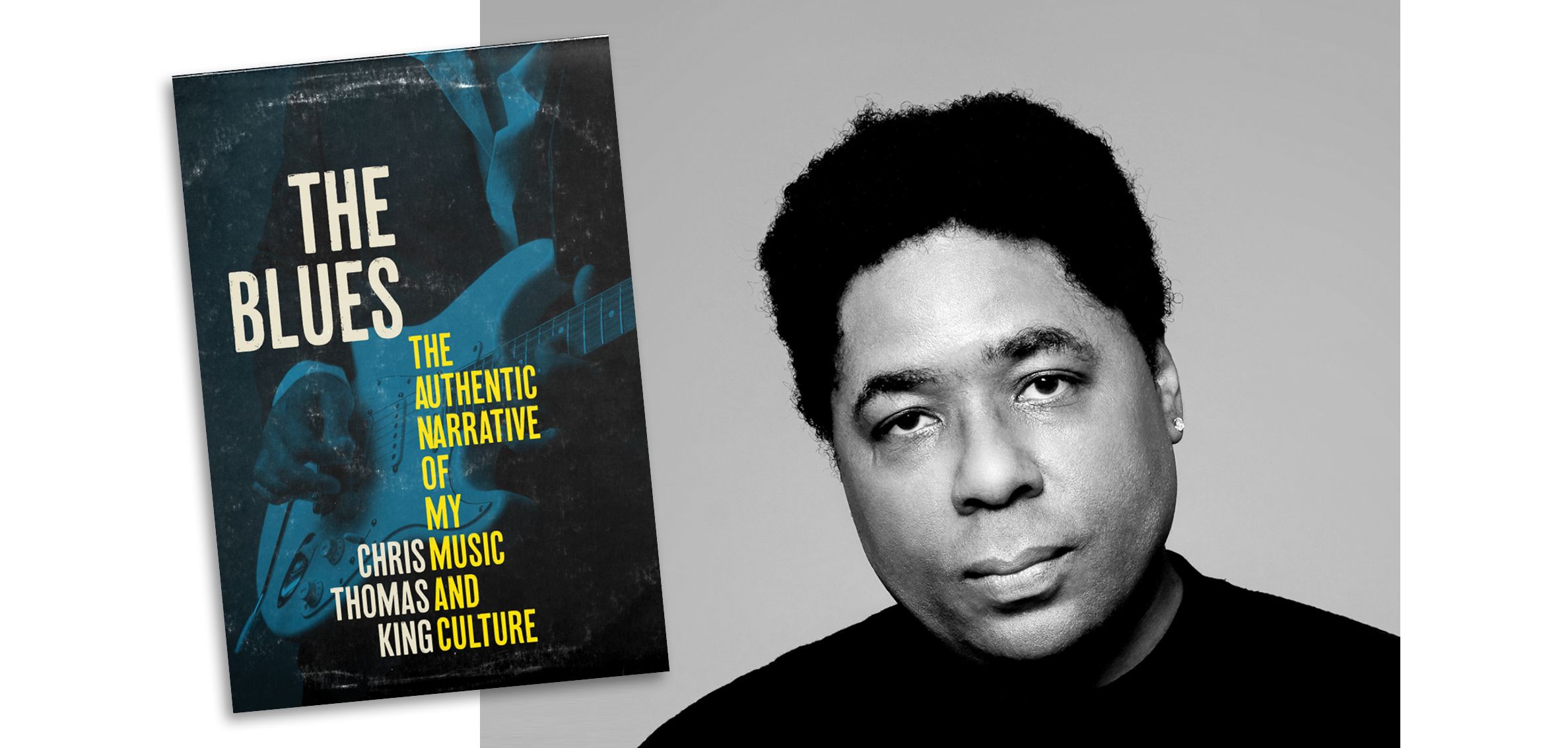

Perhaps the most widespread narrative about the birth of blues begins with Black communities in rural Mississippi, the music’s telltale groove inspired by work songs and spirituals. Famed guitarists and rock ’n’ roll heralds like B.B. King stem from this region, oft-categorized as proliferators of a distinctive “Delta blues” sound. But Chris Thomas King, the Baton Rouge-raised author of The Blues: The Authentic Narrative of My Music and Culture and son of the late Tabby’s Blues Box proprietor Tabby Thomas, follows that Mississippi Delta all the way to its mouth, embarking on a new origin story for this distinctly American genre—one that finds its roots not in the fields upriver, but in the metropolitan multiculture of New Orleans.

The 1999 demolition of the original Blues Box location and subsequent replacement by the North Boulevard railroad overpass serves as King’s metaphor for the forgotten legacy of the blues in south Louisiana. Among extensive research of the region’s anthropological histories that begot its unique cultures and musicians, King elicits that even the blues’ etymology stems from a Creole abbreviation of the French sacré dieu—or its less blasphemous counterpart, sacré bleu—a profanity likely uttered more than once by the traditional upper classes toward the new, rebellious sound in their streets. Tracing a musical legacy from classical French composers to Black Creole orchestral culture of the 1830s and beyond, along with the cultural legacy of clashing thinkers like Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois, King’s blues isn’t just academic in nature, it’s a serious business (just ask Tommy Johnson, the devil-dealing guitar prodigy King played in the Coen brothers’ O Brother, Where Art Thou?).

By the concluding chapter dedicated to his personal experience as a Black blues player in the South, his coming of age under his father’s influence, and the sheer number of musicians whose reputations reverberate across genre and time, one thing is certain: no matter where the blues ultimately came from, it will always find a home in Baton Rouge.