Fostering hope: Local foster parents encourage others to engage

Soft rays of morning sun stretch down through the oak trees at City Park as a bright-eyed baby bounces in the laps of Brandee and Rhett Sandusky. It is the first fall day the couple are sharing with this 8-month-old, and they are soaking up every moment.

Just like any other parents of a newborn, the Sanduskys are cherishing every “first” in her life. First smiles and first gleeful giggles. Patty-cake and pulling up and crawling across the kitchen floor. During this first year of life, each day brings a new reason to celebrate.

But unlike most other parents, the Sanduskys know they likely won’t be the ones to witness all of this chubby-cheeked cutie’s special moments to come. As first-time foster parents, they are committed to caring fully, but they’re also prepared for the day when they will say goodbye.

“Our job is to keep her healthy and safe while her biological parents work on being healthy,” Brandee says as the baby sits cradled in Rhett’s arms. “From the beginning, we were adamant with everyone that we were not trying to take this baby. Foster children need someone who will love them as much as they can, even though in the end there may be intense heartbreak.”

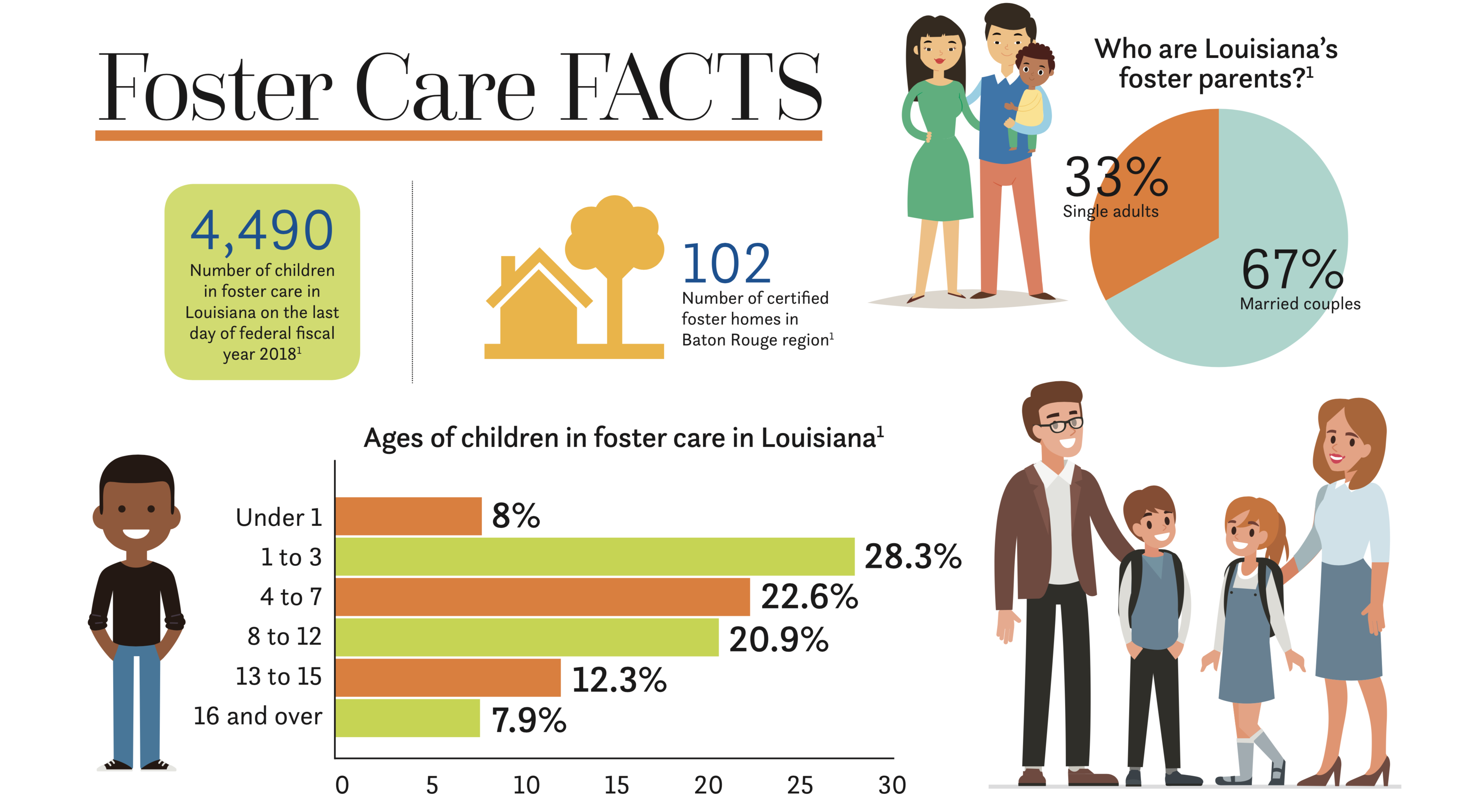

The Sanduskys are among a growing number of Louisiana adults who are becoming certified to care for children through the foster care system. Over the past 10 years, the total number of certified foster homes in the state increased from 1,654 to 2,072, according to the Louisiana Department of Children & Family Services.

These parents come from a variety of backgrounds but share a singular goal: to provide a safe and nurturing, yet typically temporary, environment for children who have been removed from their own homes.

“I loved being in the foster care classes and seeing how many different types of people were there,” says Susan Naquin, a 28-year-old single architect who became certified as a foster parent last December. “We were all different ages. We lived in different types of homes and in different parts of the city. Some had older children who were already grown. But we all felt some strong call to help.”

Naquin first felt the tug on her own heart as a young teenager when a family friend adopted two children from China. “I saw how great that was, and I knew in my heart I would do something with adoption or foster care once I was old enough and in a good place,” she says.

That feeling resurfaced when she began working at an architecture firm in Mid City and met a young boy who had been engaging in criminal mischief in the area around her office. “It really just brought back the sense that there was so much need right here in our community, and I had the means to help.”

The process of becoming certified took Naquin about six months and involved an initial orientation, several weeks of classes, the submission of letters of reference, and home visits. A week after Mardi Gras, she got a call asking if she could take a 5-year-old girl. “It was 3 or 4 o’clock on a Friday, and they brought her to me at 8 that night,” she recalls. “It was exactly like Hollywood would have depicted that moment to be: she showed up covered in dirt, her hair was knotty, and she just had a blank stare on her face.”

As with many foster children, the girl was hesitant at first to trust her new caregiver or to share her emotions. “I spent a lot of time that first week trying to get her out from under the bed,” Naquin says. “I had put a little tent in her room, and that became like a safe zone for her. It took about a month for her to really feel safe. Now she says she’s so happy—it’s a complete 180.”

Foster parents Cherith and Brandon Craft are currently in the midst of their third placement. With three biological daughters ranging in age from 6 to 12, the Crafts see welcoming foster children into their home as a way of extending hospitality and serving those in need.

“There were things going on in our city—crime, homelessness, human trafficking—that we would complain about, but we weren’t doing anything about it,” says Brandon, who owns a construction firm. “We realized that by fostering, we might not be able to change all those things, but we could make an impact on one person.”

The first children placed in the Crafts’ care were a pair of toddler siblings who stayed with them for three months. Next came a five-month stint with a 4-year-old girl. Their latest foster child, a 3-year-old girl, has been in their home since June.

“Our intentions are not to adopt,” says Brandon. “The goal is always reunification. It can be hard when they leave—there’s a little piece of yourself that goes with them—but then we know that we’ve accomplished our goal to send them back to their homes.”

Meanwhile, the Crafts have also begun forging bonds with the foster children’s biological parents—bonds that continue even after the children leave their home. “That’s been the interesting part of this experience,” Brandon says. “We thought we would be able to keep the parents at arm’s length. We thought maybe they were choosing other things over their kids. But we realized that many of the parents of children in foster care came from terrible circumstances themselves. We began to have grace for the parents, and we’ve really become involved in their lives, too.”

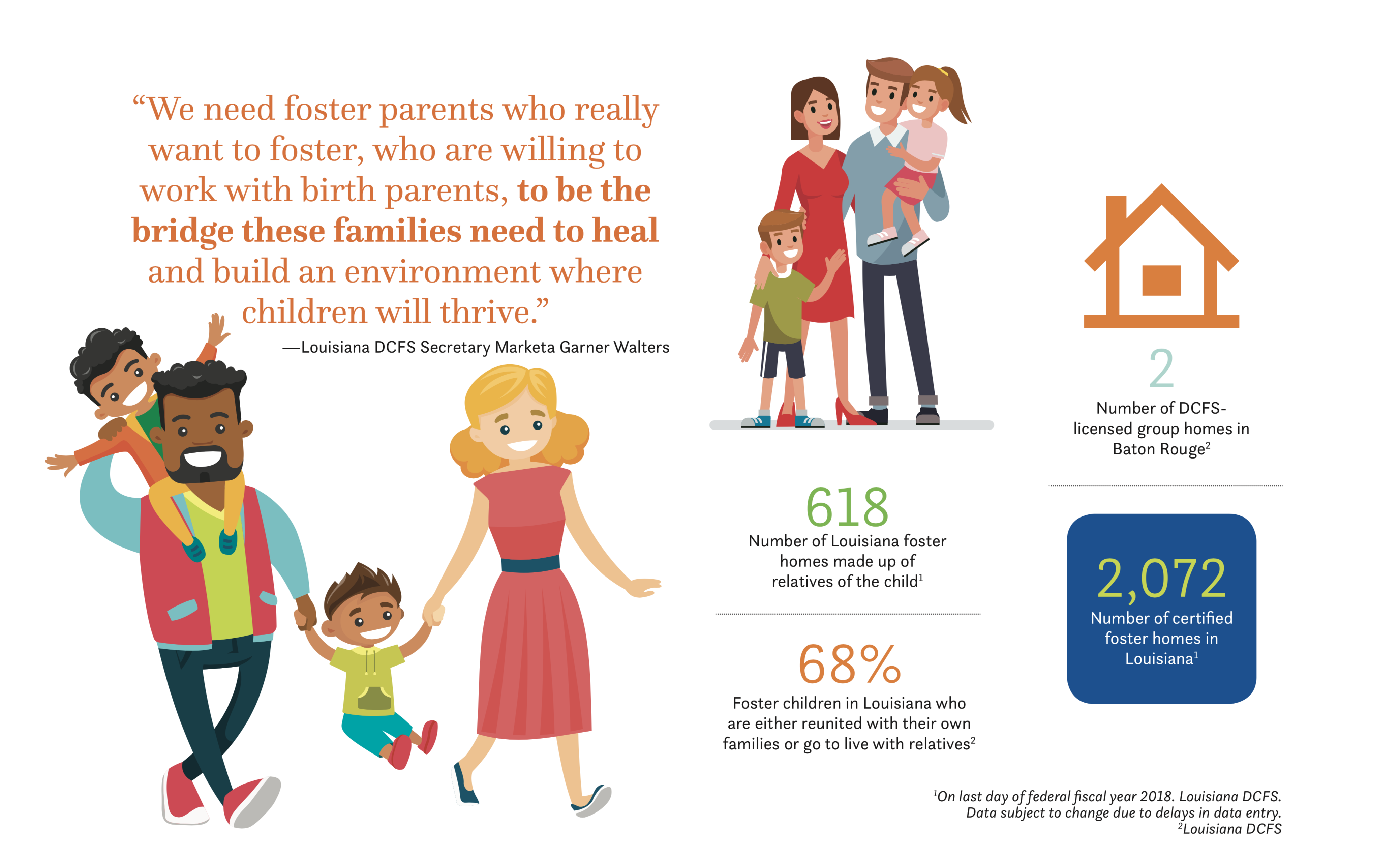

Establishing relationships between foster parents and biological parents is part of a recent seismic shift in the way the state of Louisiana’s foster care system operates. In 2016, Louisiana became the first state in the nation to adopt—on a statewide basis—the Quality Parenting Initiative, an effort to strengthen foster care by refocusing on excellent parenting and redefining the expectations of caregivers. The approach provides for closer communication between foster parents and birth parents from the moment a child is placed in a foster home.

“They used to have virtually no contact at all,” says Marketa Garner Walters, state DCFS secretary. “Now, when it’s safe to do so, foster parents are able to ask about things like the child’s favorite food, whether they have any allergies, or whether they like dogs. They get a general sense of what the child’s needs are and assure the parent that they will be attentive to those. At the same time, the foster parents can build a bond with the biological parents and help them learn to parent safely.”

QPI emphasizes that the foster parents and biological parents are part of a team, along with agency staff, working together to achieve the best outcomes for every child. The initiative also gives foster parents more authority in making day-to-day decisions for the children in their care, Walters says. In other jurisdictions around the country where QPI has been implemented, the results have included fewer unplanned changes in a child’s foster placement, less sibling separation, and more successful family reunifications.

Louisiana first lady Donna Edwards led the charge behind another recent state-level endeavor to support foster parents and improve the lives of children in their care. Building on QPI, Edwards launched Louisiana Fosters—an initiative aimed at connecting foster parents with faith-based groups, nonprofits, businesses and other potential support systems—in August 2017. (Learn more about Louisiana Heart Gallery, one of the organizations highlighted by Louisiana Fosters, in this story.)

“Louisiana Fosters is designed to help the business community and the faith community wrap their arms around foster parents so they can do their jobs better,” says Walters, noting that the program has prompted queries from multiple other states interested in doing something similar. “I think of it as a marriage—QPI is focused on how we treat foster parents and birth parents, and Louisiana Fosters is focused on how the community treats and supports foster parents and their work. It’s that blend that gives us a well-rounded approach.”

The state’s new initiatives are helping foster parents like Rhett and Brandee Sandusky navigate their first foster placement. The Sanduskys, who have been married for five years, say they felt called to foster before trying to have biological children. On the very same day they received their final approval from DCFS, they were asked if they could take in a 2-week-old girl.

It would be another two weeks before the newborn was discharged from the neonatal intensive care unit. Brandee, a 27-year-old self-employed artist, spent nearly all of that time at the hospital, with Rhett, 30, arriving daily after his work as a real estate agent. Once the baby was in their home, they jumped into what Brandee calls “full parent mode,” and at the same time she slowly began sharing snippets of their experiences with her 5,000-plus Instagram followers.

“We decided to document our journey because being a foster parent is so beautiful and so many people don’t know much about it,” she says. “We saw it as a great opportunity to show that this is possible and that there’s such a great need. We hoped that other people might feel called to do the same thing.”

In her social media posts, Brandee has been candid about the emotional struggles that come along with caring for a child in the foster care system. “We pray little one leaves us,” she wrote in one post. “Tearful prayers. Because it’s so sad to think about. But what a miracle if she does leave us. What a beautiful redemptive story that they get to share and have forever.” Friends and strangers alike have responded positively to the couple’s online testimonies. “I’ve received direct messages from people here and in other states, asking questions about the process or saying they were going to start taking foster care classes,” Brandee says.

She and Rhett felt inspired to host an informal foster care information meeting at their home during the spring, and they were overwhelmed by the number of people who attended. “We plan to have more of those, because there are so many children who need foster homes,” she says. “We get calls regularly asking if we can take another child. We want others to come along and say yes to foster care, because honest, loving, selfless foster parents are so needed.”

Brandon and Cherith Craft are also looking beyond their own service as foster parents to try to support the system as a whole. “We asked ourselves, how do we help make a more lasting impact rather than just what we’re doing in our own home?” Brandon says. “We’ve seen how hard it is for the social workers—they all have a heart to serve, but they’re drowning. The system is overloaded.”

The Crafts have begun taking small steps with the simple mission of helping to make DCFS social workers’ jobs a little easier. Noting that more than half of children return to their biological parents after being in foster care, Cherith recently coordinated a project to provide more than two dozen “Welcome Home baskets” to those families. The baskets, which were assembled by local church groups and families, contain basic household items from cleaning supplies to towels to boxes of macaroni and cheese.

To further this work, Cherith was recently selected to be an advocate for The Forgotten Initiative, a faith-based program that helps create foster care ministries in communities around the country. “As an advocate, I will meet regularly with our local DCFS offices to find out the needs in our area,” she says. “My role from there will be to mobilize our churches and community into action to meet those needs. Churches are already poised to do this; the Bible tells us to care for widows and orphans. We just need to get everyone together to figure out how to do it most effectively.”

Even as they think of the bigger picture, local foster parents are also working to change personal perceptions about the foster care process, one conversation at a time.

Even as they think of the bigger picture, local foster parents are also working to change personal perceptions about the foster care process, one conversation at a time.

“People say they worry that they would get too attached,” Rhett Sandusky says. “Obviously, when you spend every second with a child, you get attached. You put a lot of work in and love in. But you have to remind yourself of the reason you got into fostering—to help these families who are going through a tough time.”

Adds Brandee, “If you think you can’t emotionally handle it, you’re probably the perfect person for foster parenting. A child needs someone who will give selfless care 100%, someone who gives all they can give, not someone who only gives 15% because they don’t want to get hurt.”

Susan Naquin says she tries to remind people that foster parenting is not a superhero’s job.

“I get a lot of ‘She’s so lucky to have you’ and ‘You must be the best mom,’” Naquin says. “But I still struggle with things like getting her to bath time. The journey is hard but it’s also regular. We’re regular parents, just like any other parents in this city. But the kids still grow so much, even though we’re not extraordinary.”

Naquin says being a foster parent has changed her own life “in every way possible.”

“I don’t think I can go back to being who I was before,” she says. “It’s definitely taught me how to manage my time and resources, and how to be thankful for that time and those resources too. But I also feel like my life is going to be a lot less exciting when she’s gone. Right now, my house is filled with love and laughter. There are coloring sheets and toys everywhere. That has been a welcome thing that I will miss. Until I take in another child, it’s going to feel a little empty.”

She pauses, then smiles. “It’s changed everything.”