A Congolese refugee anticipates a long-awaited reunion thanks to the help of local friends

Louisiana-shaped pendants dangle from Lilly Mujinga’s ears as she sits in a shady spot outside The Hope Shop. For nearly seven years she has lived and worked in Baton Rouge, including in this Government Street gift store where fellow refugee women create small crafts to sell among clothing and home goods from around the world. But today is Mujinga’s day off from her new job with LSU’s custodial department, and she sits at a tea table and notes the mild weather, which reminds her of home in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Good news has landed on her lap just this morning. After much paperwork and almost three-quarters of a decade apart, one crucial family member may soon be making a journey of his own to join her in the Pelican State.

“Permission for my husband to come here has been approved,” she says.

Born in the south of the Congo in the province of Katanga, and later living in the city of Mbuji-Mayi, Mujinga once eked out a living selling what she could amidst the dangers of the First and Second Congo Wars. But by the 2000s, after reckoning with violence, tribal prejudice and a rising death toll that would later elicit the wars’ reputation as the deadliest global conflicts since World War II, she knew she couldn’t stay any longer. In 2003, in her mid-30s, Mujinga became one of the millions of people to flee the country known once for its glimmering rainforests and hills of precious metals. She eventually settled in a refugee camp in Zimbabwe, where she remained for 13 years.

“In Congo, there was a lot of insecurity. Rebels were killing people, raping people… Finding a job was difficult. Everything was difficult,” she recalls. “People were always scared, because anything could happen.”

But camp life wasn’t much better, with Mujinga eventually divorcing her first husband, with whom she had traveled. She watched him depart for another camp in South Africa, where some of her relatives still live. In 2015, though, she met her current husband, Ezekiel Sibinwa. Things were starting to look up. Having begun her application for resettlement in 2013, three years later she was nearing the end of the process.

“They would put up the list of approved applications at the camp, and everyone would go to read,” says Mujinga. “One day, I found my name there. America had chosen me. But I was not happy.”

With approval, after all, came one distressing caveat: Sibinwa, who met and married Mujinga after she began the resettlement process alone and thus could not be added to her application, would not be able to join her in the United States. Not yet, anyway.

Once in Baton Rouge, Mujinga began receiving assistance from Catholic Charities, whose volunteers helped her figure out the paperwork she needed—including her official certificate of marriage, which she would need to travel back to Zimbabwe to claim. She also began taking the free conversational English classes that have been offered by The Chapel on LSU’s campus for 30 years. Through those classes, she met Amber Elworth, the future owner of Light House Coffee who volunteered as an ESL teacher at the time.

“She asked me about my case, and I explained the story about my husband,” says Mujinga, who was later employed at Light House Coffee for about four years. “She was shocked. She wanted to do something to help.”

In time, Elworth and other friends of Mujinga, including Hands Producing Hope founder and The Hope Shop owner Rebecca Gardner, raised enough money to surprise Mujinga with a trip back to Zimbabwe to reclaim her marriage certificate, reunite with her husband for a month, and return with the materials needed to begin his resettlement application for the United States.

“I was drawn to Lilly because she was here alone and had no family, whereas most people I saw coming through for classes had at least a spouse or a child with them,” says Elworth, who helped teach the six “survival English” courses required of refugees seeking to receive assistance checks. “My heart really went out to her.”

For Elworth, who employs multiple displaced people at Light House in order to provide a safe, welcoming space for them to become acquainted with American culture and language, the weight of what refugees have experienced can be difficult to put into words, despite her close proximity to their lives.

“When refugees leave everything to escape to neighboring countries, for example, sometimes they have to burn all their government documents—their passports, everything—which really puts them in a bind,” she says, noting too the violence often dealt upon family members left behind, from beatings to murder. “The experience is very hard to compare to anything in the life of someone who has never had to deal with that. But it challenges me to use my time and energy in ways that can help, and not be so self-consumed. We just want to love on these people and give them genuine hope. Not as this big charitable thing, but because we care about them and know that what they’re going through is awful.”

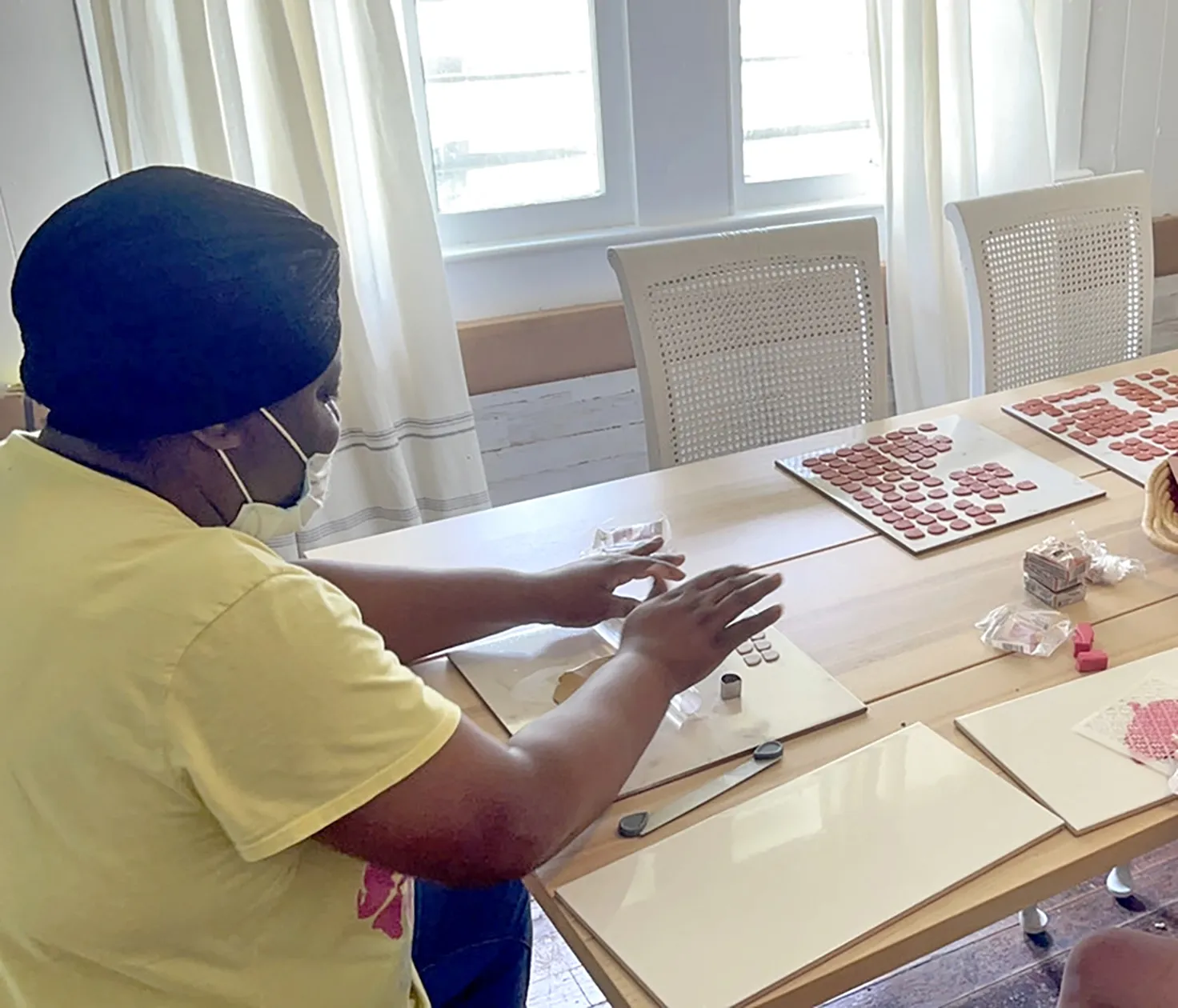

Building friendships and a sense of purpose can often be the first step to creating a new identity, which is why Rebecca Gardner founded Hands Producing Hope in 2012. Originally begun as a partnership with female artisans in Rwanda and Costa Rica to help sell their crafts and increase quality of life, Gardner eventually turned her eye to the refugee community in Baton Rouge in 2016, when she first met Mujinga via her acquaintance with Elworth. Through the organization’s Re:Build program, Gardner provides artisan training, additional income, transportation resources and the emotional support of community to refugee women new to Baton Rouge. They gather regularly in the crafting room in the back of The Hope Shop, the retail space where Gardner sells locally made creations from clay jewelry to intricate macrame décor.

“We practice English together, just explaining different phrases and words as they come up in conversation while we’re working,” says Gardner. “We’ll help them call and make doctor’s appointments or mentor them through career dreams and citizenship application processes. Every woman is different—some come from poverty and some come from a middle-class family that owned a house and worked a good, stable job—but we’re all banding together to help rebuild the lives they lost through no fault of their own.”

In Louisiana, Mujinga, a native French speaker, occasionally met someone involved with The Chapel’s ESL program who could speak with her in the language of home. But even those teachers who encouraged her in the earliest days of her residency—when Mujinga says she felt most afraid and alone due to the language barrier—continue to offer assistance not because they want to eliminate differences or play the hero, but because of the privilege that comes with learning someone’s unique story.

“At one point, Lilly admitted that she was riding the bus an hour and a half both ways from her apartment off Government Street, so eventually I started picking her up before class and dropping her off afterward, which is how I got to know her a bit better than many of the other students,” says Nancy Hicks, a retired teacher and one of Mujinga’s early English tutors at The Chapel. “The students are just so grateful to be there. They’re learning from you, and you learn so much just by going to get coffee with them and hearing their stories. I can’t imagine stopping.”

For now, Mujinga must continue to submit pay stubs for scrutiny over the next few months. Then her papers will be sent to the embassy in Zimbabwe, where she will sit for an interview. “If they approve, then they start the process for my husband,” says Mujinga, “and in six months he can come to America.”

When asked if she ever imagines herself back in the Congo, Mujinga looks off into the distance, waiting a few beats before answering.

“In Congo there is still no peace,” she says. “Even now. No peace.”

She sees, instead, her continued life here in Louisiana, this time taking on the mantle of the teacher for herself when Sibinwa finally steps foot on American soil. With her own experience guiding her, she says, she can help him succeed. Of course, she adds, she owes so much of that experience to friends and helpers she met along the way.

“I’m good now. I’m safe. I get what I need,” says Mujinga. “I have friends that God gave me. Any problem I’ve had, they’ve helped me find a solution. And they’ve become like family.”