Reflecting on the Baton Rouge bus boycotts 70 years later

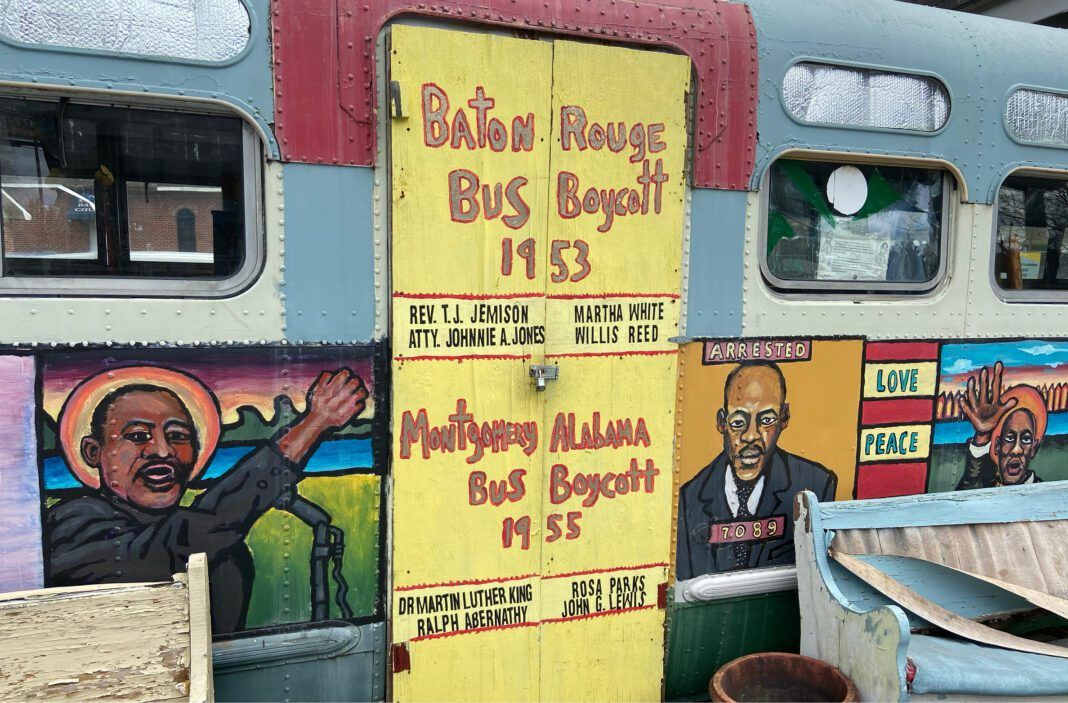

Racial tensions had been boiling in Baton Rouge long before June 15, 1953, but on that sultry day in Jim Crow’s South, one woman’s small rebellion would spill over into an oft-forgotten, but crucial moment in the burgeoning civil rights movement. Not that it had been planned that way. Martha White, a Black housekeeper traveling home via the city’s public bus system, hadn’t intended to spark a multi-day bus boycott when, tired from a long day’s work on her feet, she sat down at the front of the bus’s whites-only section—the only place where sitting was even possible. No model yet existed for such an act. After all, Rosa Parks wouldn’t cause a stir in Montgomery, Alabama, for two more years, though she had likely seen Baton Rouge in national headlines, as had a certain young preacher named Martin Luther King, Jr., who would soon meet with Baton Rouge leaders during the run-up to his groundbreaking 1955 Montgomery bus boycotts.

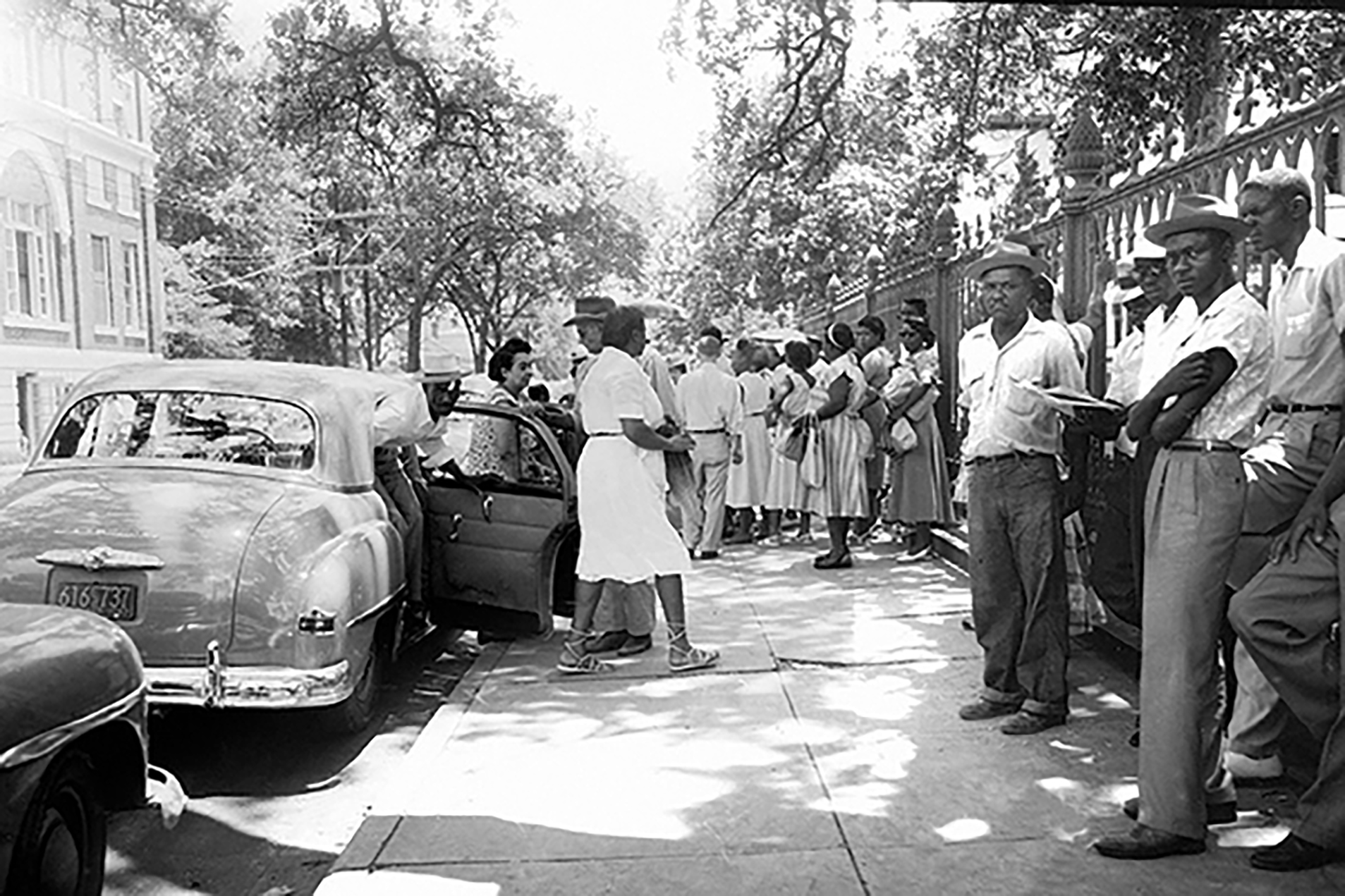

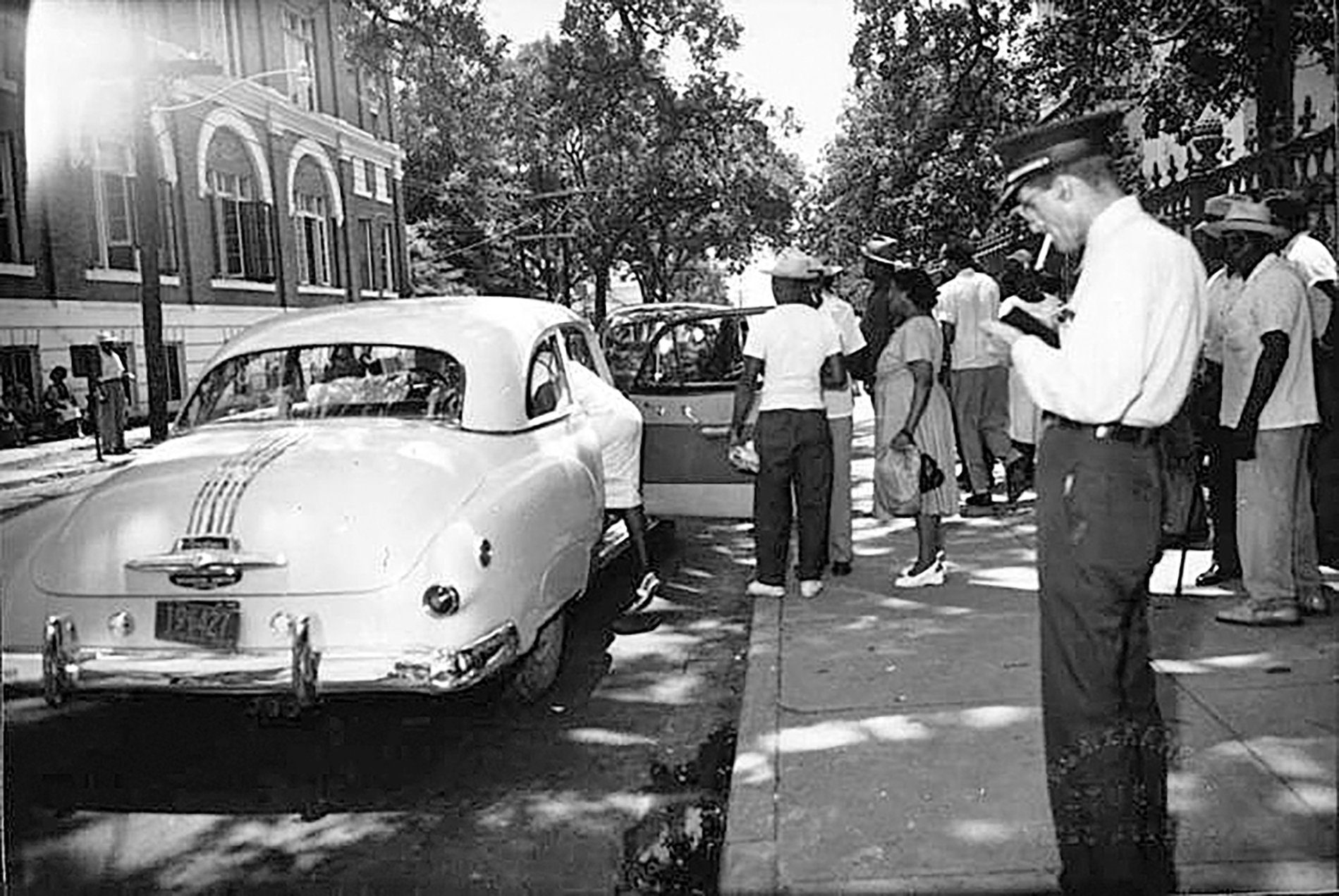

Still, when White found herself ejected from the bus, victim to a segregated transportation system that had long exhibited prejudice against Black individuals and business, she also found company. Since 1950, Black residents of Baton Rouge had been dismayed by the city’s bus service after the city council revoked the licenses of several independent, Black-owned transportation companies. Then, a few years later, the city increased bus fares—the same fare for all passengers despite the fact that Black passengers were not allowed to sit or be near white passengers—furthering the indignity cast upon the 80% of the city’s public transportation users. White’s experience with discrimination was the last straw. Black riders boycotted the buses altogether, setting up a carpool service intended to kick the city where it hurt the most: its pocketbook.

The protest gathered a new cast of characters into the plot of what would become known as the first large-scale anti-segregation bus boycott in the United States. Take, for example, the charismatic Rev. T.J. Jemison, a relative newcomer and pastor of Mt. Zion First Baptist Church—at the time one of the largest and most influential Black churches in Louisiana. According to a 1995 oral history collected by the McKinley High School Oral History Project, Jemison became the face of the boycotts after personally witnessing White’s ejection in June: “Whenever you hurt them, you hurt me,” he told the responding officer trying to direct him away from the scene. Jemison had already engaged with the broken public transportation system months earlier, appearing before the city council to decry the fare increases and contribute to Ordinance 222, which changed the bus seating to a “first come, first served” model that nonetheless still required Black passengers to enter from the back, and white passengers from the front.

Civil rights attorney Johnnie Anderson Jones Sr.—a Southern University graduate, Purple Heart veteran of World War II, and the first Black U.S. Army warrant officer—also joined the cause, serving as legal counsel and writing a brief that would eventually reappear in the 1956 Birmingham bus boycott pleadings. Long after the protests’ end, Jones continued to fight for equal rights from a legal and personal perspective, facing a scourge of dangers at the cost of integrating Baton Rouge’s pools, parks and other public spaces, and later serving as a Louisiana State Representative.

One might say that his vision for a more equitable America looked like that of fellow collaborator Horatio Thompson, a prominent Black businessman who owned several Esso gas stations and provided fuel to boycotting carpool drivers at cost. Of his number of customers, many likely boasted membership in the newly formed United Defense League, a coalition of Black activists formed in tandem with the protests and led by Jemison and other community leaders including executive chairman Theodore Roosevelt Smith Sr., whose grandson Russell L. Kelly Sr. continues to serve as one of the boycott’s unofficial historians in present-day Baton Rouge.

“Some of the oaks outside of the Old State Capitol today,” says Kelly, who also maintained a friendship with Jones until Jones’ death in 2022, “are the same ones that shaded the protestors while they waited for their buses—or for their rides during the protests. Baton Rouge is a place where history happened.”

Contemporary residents can also see homage paid to the protests at a plaque outside McKinley High School Alumni Center, a site chosen by the Toni Morrison Society’s Bench by the Road Project to commemorate important events in African American history. Likewise, the Capitol Park Museum houses a permanent exhibition on the boycotts. Lori Martin, an LSU professor and one of the Toni Morrison Project’s local committee members, underlines the significance of such historical preservation in her book South Baton Rouge, co-authored with MetroMorphosis’s Raymond Jetson to include details on the city’s history with social justice movements.

“There are only about 30 Bench by the Road sites in the United States, so it’s very significant not just in terms of the boycott’s place in history, but also Baton Rouge’s role in history,” says Martin.

Even so, the weight of the protest wasn’t yet the perfect storm required to end segregation altogether.

“Johnnie Jones said that Baton Rouge initially missed its place in history because the boycotts ended prematurely,” adds Kelly, referencing Jemison’s ultimate negotiation that still maintained segregation on public buses, directing Black riders to board from the back and white riders from the front, with the races unable to sit beside one another in the same row. Even today, many argue that Baton Rouge still has large strides to take in the realm of transportation equity, from inconvenient bus schedules to the lack of overhead shelter at many bus stops.

“There are still challenges, like some neighborhoods not wanting sidewalks so that they don’t invite certain people in, or the continued difficulty of building a train from Baton Rouge to New Orleans,” says Martin, who has also experienced the system’s shortcomings firsthand. “When I moved here in 2013, some of my son’s teammates who lived near us on Gardere would take the public bus home, and it would take hours. Something as simple as trying to participate in youth sports or to simply go to work shouldn’t be so difficult, and that’s not always a coincidence.”

Historically speaking, however, the psychological impact of the boycotters’ gumption made its mark, reverberating into the successive boycotts and ridesharing movements under King’s leadership in Alabama and beyond. Seventy years later, that history has not lost its significance.

“It wasn’t just the buses. It was the experience of living under that kind of segregated regime,” says Martin. “These were just regular folks who decided that they weren’t going to take it anymore.”