Later gator: Artist Leslie Charleville draws upon ancient technique to immortalize swamp and Gulf creatures

With the glancing beams of the closest car falling soft on the wood planks and lazy waves below as her lone source of light, Leslie Charleville crouched in the dark cloak of the Orange Beach Marina and went to work, a wet paint roller in one hand, paper towels in the other. Before she even put brush to fin, she knew that making a late-night print this large in this humid haze would be the greatest challenge of her career.

At eye level was the mountainous ridge of a bluefin tuna, and her hands on the giant fish looked almost like they were folded in prayer. The fisherman called it a 700-pounder when she got the assignment, though they do tend to round up from time to time. Regardless, it was “a hell of a fish,” Charleville recalls.

The 44-year-old creative serves as director of special events at the Louisiana Art & Science Museum, but she’s become increasingly known in rural communities and fishing outposts across the bayou for making memorable animal art on the spot. Before she could set off for the museum that morning, she received a 6 a.m. call from a satellite phone out in the Gulf. They had just hauled in the huge tuna and, knowing Charleville by reputation only, they rang her wanting a print.

“Let me just make sure I have enough supplies and canvas, and I’ll be there,” Charleville replied, before leaving for coastal Alabama and the next chapter of her not-so-secret career as a wildlife artist.

Always prepared to venture out to a dock near or far, Charleville keeps a ready bag stocked with clothes, paints, inks and a variety of textiles, both at her home in rural Rosedale and at her office in downtown Baton Rouge. She uses gyotaku, an ancient Japanese practice of ink and canvas impressions that result in richly textured prints of fresh catches, and even Louisiana’s most infamous reptile, her favorite creature to feature.

“I’ve been all over the state just chasing alligators,” Charleville admits.

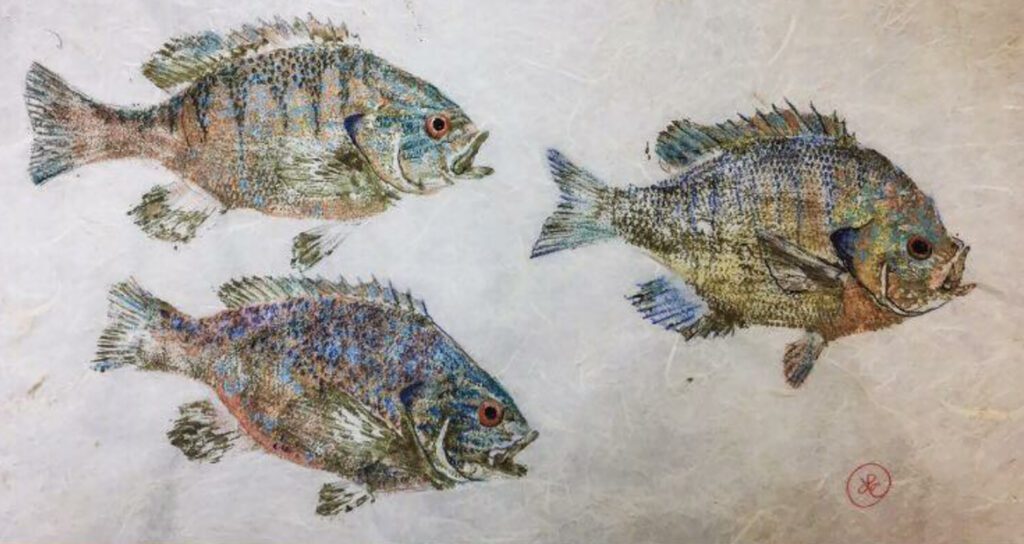

Gyotaku dates back to the mid-19th century, when fisherman toiling along the coast of Japan covered their catch in sumi ink and rubbed them into rice paper to catalog the day’s produce so their business partners know exactly what they were getting. Despite these folkish commercial roots, artistic embellishes like calligraphy, coloring and chops—classic red seals—soon washed into the practice.

Though she mixes things up with various linens, muslin and canvases, Charleville loves this kind of classic, direct gyotaku printmaking for its realness, its ability to capture a moment otherwise forgotten.

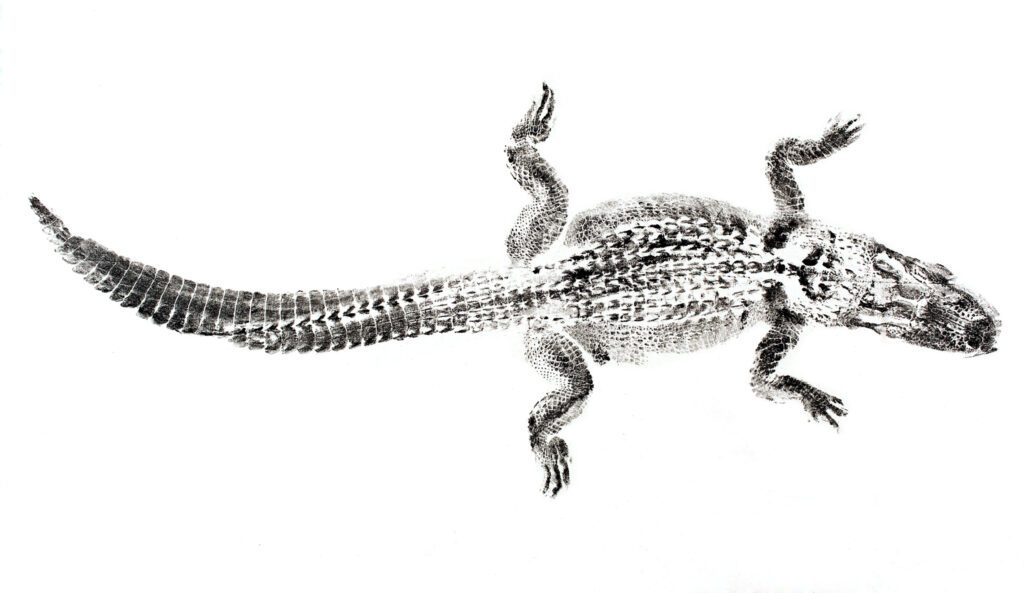

Not unlike Japanese fisherman more than a century ago, preserving every overlooked subtlety of these animals is important to her, because the prints show her community exactly what we have. Underappreciation be damned, these little beasts are beautiful.

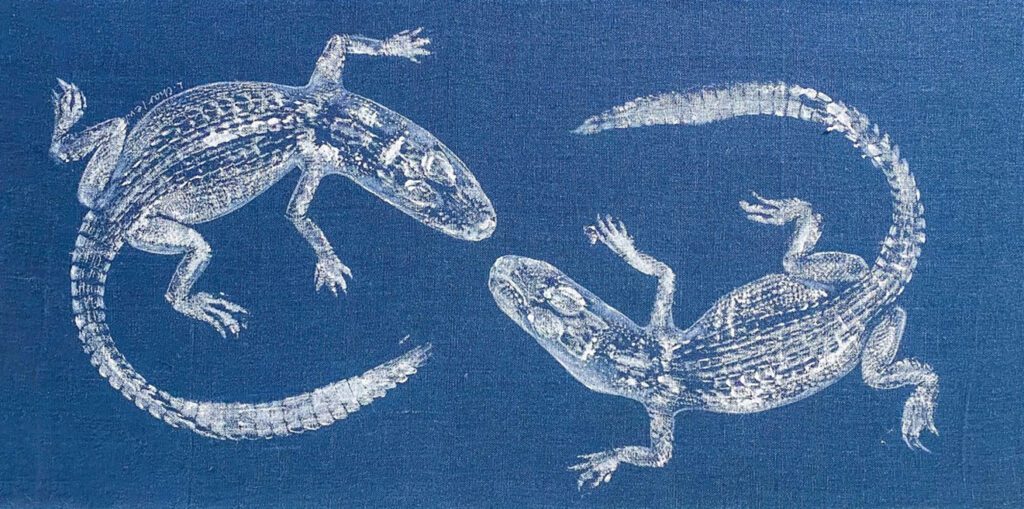

“This alligator would have been harvested, cleaned, consumed then forgotten, but not this one,” Charleville says, unrolling a dark blue duck canvas to reveal a striking alligator image inside the kitchen space at the LASM. “It’s here, right here, and its DNA is in this art forever. And look, there’s some little imperfections, but this is exactly how it was, his little toenails there. It’s pure. I’m not doing anything else to this one. I’m not going to touch it at all—why would I?”

Charleville grew up barefoot, hunting and fishing on the edge of the Atchafalaya in a small village called Rosedale. On her parents’ farm, she learned that all animals have a purpose and a value. Lambs and baby pigs needing care were shuttled into the house in laundry baskets and bottle fed until they gained their strength. Charleville remembers giving visiting deer Tootsie rolls and waking early to follow her father around on chores. It’s no wonder that her artwork has always been animal-focused. They are her experience.

“Honestly, I thought I knew what an animal looked like, but I had no idea until I started printing,” she says. “I began noticing every intricate detail.”

Frances Lee is LASM’s director of communications and operates Charleville’s website. She’s seen how the artist’s small-town upbringing helps her connect with a wide-ranging clientele.

“Just like her artwork, which has such broad appeal, Leslie can relate to anyone—from art historians to Cajuns on the bayou,” Lee says.

Once nearly anonymous behind her eye-catching animal prints, Charleville is beginning to gain more recognition as her connections and word-of-mouth recommendations spread. Hey, you’re the Alligator Girl! is a call-out she’s likely to hear at church and at The Chimes.

Charleville gives her gators playful names like Baptiste, Celine and Rita. They’ve filled local restaurants and homes, and in early 2021 she sold pieces to California and North Carolina, with more planned to hang in a restaurant there soon. Going “coast to coast” was a big step for her, she says.

Despite the increased spotlight on her work now, Charleville remains a small-town girl at heart. She commutes from Rosedale daily. Whether watching the final whispers of a sunrise across I-10 or bumping down dirt roads with a line of tin-roofed fishing camps growing in the distance, driving is her quiet time for personal reflection, her time to recharge.

While the colors of kudzu and moss, morning dew and oak groves blur together on the road, Charleville clears her mind and focuses on connecting with the clients and the animal.

“It’s all about arriving at that moment where it’s just me and the animal, just nature,” Charleville says. “It’s a journey of getting to this point of stillness. And when I’m there finally, it’s this feeling of arrival.”

Charleville’s sacred approach to gyotaku is evident in the feel of the final pieces. That’s why lobbyist and avid outdoorsman Ty Bromell asked the artist to print a large red snapper he caught down in Venice.

“It really brings your outdoor experience to life,” he says of the piece. “You’re able to share your harvest through her art. Leslie came to my home and let my daughter Ellie help out, and that has made Ellie more fond of the arts.”

The experience of having a catch rendered in a work of art also sheds a new perspective on hunting and fishing, Charleville believes. She hopes her work can spread more mindfulness and reverence for the animals we eat.

“You’ll see pictures of people with their catch or kill, and the whole message is ‘I dominated this,’ and I don’t want my art or photos of me with a gator to look like a trophy,” Charleville says. “It’s respectful. This is part of my life, and the animal and I are both worthy aspects of nature.”

Though she wishes she could have moved that giant bluefin tuna to a dryer spot at the marina, nothing could roll that hefty fish, and Charleville did her best. As she worked through the murky Orange Beach evening, her feet slippery with fish blood, a large crowd gathered to watch her print, transfixed silhouettes in the headlights.

“Nothing like a little pressure to make you step up your game, right?” she says. “I like how it turned out, and it ended up a great experience.”

Though Charleville wants to expand into paper goods and licensing of her prints soon, she’s done well so far with direct sales through her website and by taking commissions—all without gallery representation.

“Her passion for it creates something not only beautiful but important,” says Cindy Verdin, a friend and frequent accomplice on printmaking adventures. “It’s about awakening the imagination of the outdoors.”

Perhaps Charleville has eschewed galleries because the artist who hustled wounded lambs into her home as a little girl still sees herself as more of a caretaker than a fine artist, motivated by the importance of documenting and celebrating the often-overlooked wildlife that share a biosphere with us here in south Louisiana.

Maybe she’s more comfortable in shrimp boots than high heels.

Working closely with these animals has taught her a lot. She can name any Gulf fish after a quick look at the fins. But more than that, it has given her a fresh perspective on herself and her creativity.

“I’ve learned so much, because now I feel a sense of responsibility to really honor the animals with all that I do,” Charleville says. “It’s like I’m one with it all, and I see the true purpose in being a part of this circle of life.”