The Huey P. Long Field House comes back to life after decades in disrepair

The Tiger faithful don’t need a DNA test to find out where they come from.

Tailgates are filled with stories about how generations of family members met their match on LSU’s campus. For families who trace their Tiger pedigrees back a half-century or more, that place of origin is likely to be the Huey P. Long Field House.

From 1932 until the mid-1960s, the events that took place at LSU’s first student center stimulated a sense of community on campus and defined the culture and character of the university. However, as its 90th anniversary approached, the iconic building was desolate and largely invisible to the campus community.

Fortunately, with a ribbon cutting ceremony this October, the Huey P. Long Field House officially returns to its roots at the center of student life, regaining its place of prominence on Victory Hill.

The ravages of time, deferred maintenance and lack of funding were significant barriers to rehabilitating the LSU landmark. But, ironically, the biggest challenge for the building—named for a larger-than-life Louisiana personality—was overcoming an identity crisis.

After being elected governor in 1928, Huey P. Long was determined provide LSU students with an education and amenities that bested other state schools.

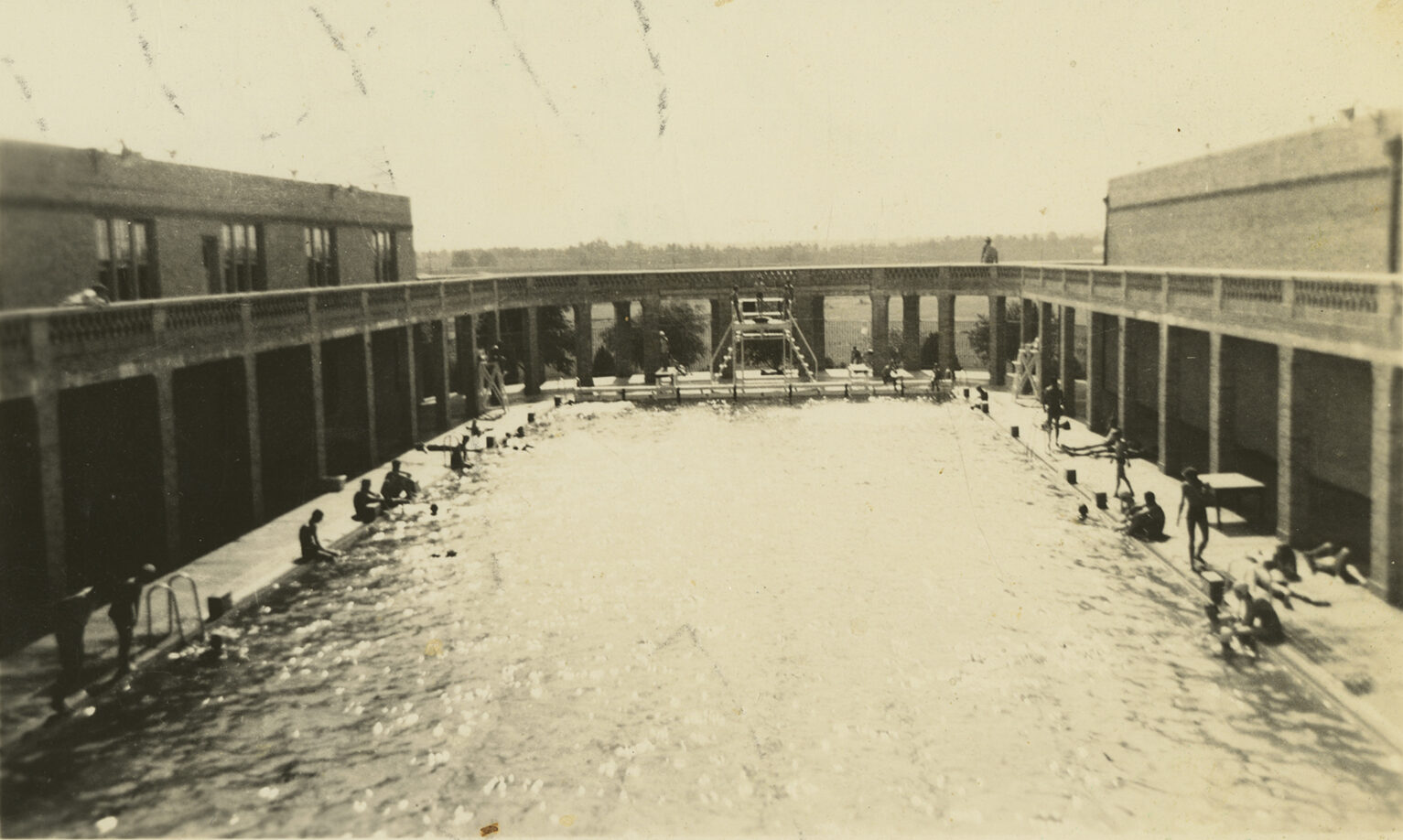

Completed in 1932 during the Great Depressions at a cost of $1 million, the Huey P. Long Field House’s opulent decor included arguably the first use of a roaring tiger in the relief above its entrance and the mosaic on the floor of the foyer. Its grand ballroom featured chandeliers, patterned terrazzo, corbels, marble wainscot and arched windows that led to a second-floor gallery overlooking the Greco-Roman-style pool, which was then the largest pool in the country. The massive building also housed a soda fountain, dormitories, student lounge, post office, barber shop, beauty parlor, cafeteria, women’s gymnasium and racquetball and handball courts.

The elaborate structure quickly gained a regional and national reputation as an events venue hosting military balls, tea dances, homecoming and even intramural sports. The pool provided swim classes for area kids and physical therapy for polio survivors and disabled children. For nearly 50 years, fraternities and sororities staged extravagant water pageants with the proceeds going to local nonprofits.

But, as LSU professor of kinesiology Chad Seifried explained in a 2014 article published in Louisiana History, the construction of the Student Union in the 1960s, Carl Maddox Field House in the 1970s and UREC in the 1990s siphoned off student life from the Huey P. Long Field House. By 2000, LSU’s chancellor declared the building an “uninhabitable space” and in “such terrible disrepair that we have abandoned it.” Eight years later, The Foundation for Historical Louisiana included the landmark on its Treasures in Trouble list.

Even in a dilapidated state, it remained an iconic feature of campus—as evidenced by its cameo in the blockbuster Pitch Perfect. But it would take a lot more than a movie for the Huey P. Long Field House to return to relevance. By 2020, the building had faded into obscurity for an entire generation of students.

Still, the landmark never completely lost its mystique.

“The thing that’s so telling about this building is how sentimental people get about this space, especially the ballroom and the pool,” says Roland Mitchell, dean of LSU College of Human Sciences & Education, whose headquarters are in housed at the Huey P. Long Field House. On tours, donors, faculty, alumni and other stakeholders often point out where they had the first kiss or dance with their spouse, worked their first job as a lifeguard, played racquetball in “the Dungeon,” met for fraternity or sorority step practice or snuck in on a dare.

The idea to renovate the site gained momentum with the founding of LSU College of Human Sciences & Education in 2012.

After languishing on the state’s list of buildings to gain preliminary funding for 15 years, the project received legislative approval for $1.8 million for design in 2016. But those funds weren’t available until 2018.

When raising substantial private donations proved to be a daunting task, Mitchell convened an advisory group.

“We realized it wasn’t just about this building,” Mitchell explains. “We had to communicate how securing the resources benefited the entire community given our quality-of-life mission.”

LSU College of Human Sciences & Education’s six schools educate professionals who anchor and care for communities including teachers, social workers, mental health advocates, wellness experts, workforce development professionals and information specialists.

“We improve communities collectively and comprehensively,” Mitchell says. “Once we got that message together, it wasn’t hard to get the university, the state and the broader community behind us.”

That message and the prospect of the renovation resonated with local attorney and real estate developer Russell Mosely, the great-grandson of Huey P. Long. The LSU alum volunteered to work with the legislature, governor’s office and bond commission to pursue funding in the capital outlay, so the project didn’t have to rely solely on private dollars.

With funding approved by the State Bond Commission in 2019, the project advanced to the construction stage. By then, 70% of the building was shuttered. The schools of social work and kinesiology inhabited the remainder, which consisted largely of a hodgepodge of office spaces, classrooms and a warren of sci-fi-worthy science labs.

Led by architectural teams from Tipton Associates and Remson Haley Herpin Architects in association with Gensler, Arkel Constructors started demolition in early 2021.

“The restoration was about bringing the building back to life and returning the character, excitement and student-centric energy that it was born for, so it could again take its rightful place in the campus experience,” explains Kenneth Tipton, architect/planner and managing principal at Tipton Associates.

In addition to renovating and repurposing the existing space, the architectural plans also integrated a new addition to increase the college’s access to state-of-the-art classroom space and labs.

“For our family, the renovation of the Huey P. Long Field House is a symbol of rebirth of part of LSU’s campus,” Mosely says.

Like his great grandfather, he asserts a quality faculty and campus remain the key to keeping the best and brightest in Louisiana. “If we’re going to compete in modern-day education, we need to cherish our flagship university and continue investing in LSU, its facilities, faculty, students and buildings,” Mosely says.

As the father of two college-bound teenagers, he hopes the revitalized building will endear LSU to new generation of students.

“I want students to have fond memories that were formed here,” he says. “Hopefully, they build family legacies of caring about LSU, as a result of their time in this newly renovated building in the center of campus.”

Mitchell says the challenges of restoring the tiger mosaic and the iconic building’s roar helped solidify the college’s purpose and persona for the future.

“This building was originally part of the second phase of construction for LSU. And what better name than Huey P. Long given that he was so ambitious in everything he did for LSU and Louisiana,” Mitchell says. “Part of us living up to that legacy is we have to be audacious in setting goals for what we can achieve for the community. This building is not a mausoleum. It commemorates what we were founded on; but, it launches us into the future as a land-grant university prepared to meet our responsibilities to our constituents, people in the region and even across the globe.”