Squad goals: The high-flying world of competitive cheerleading

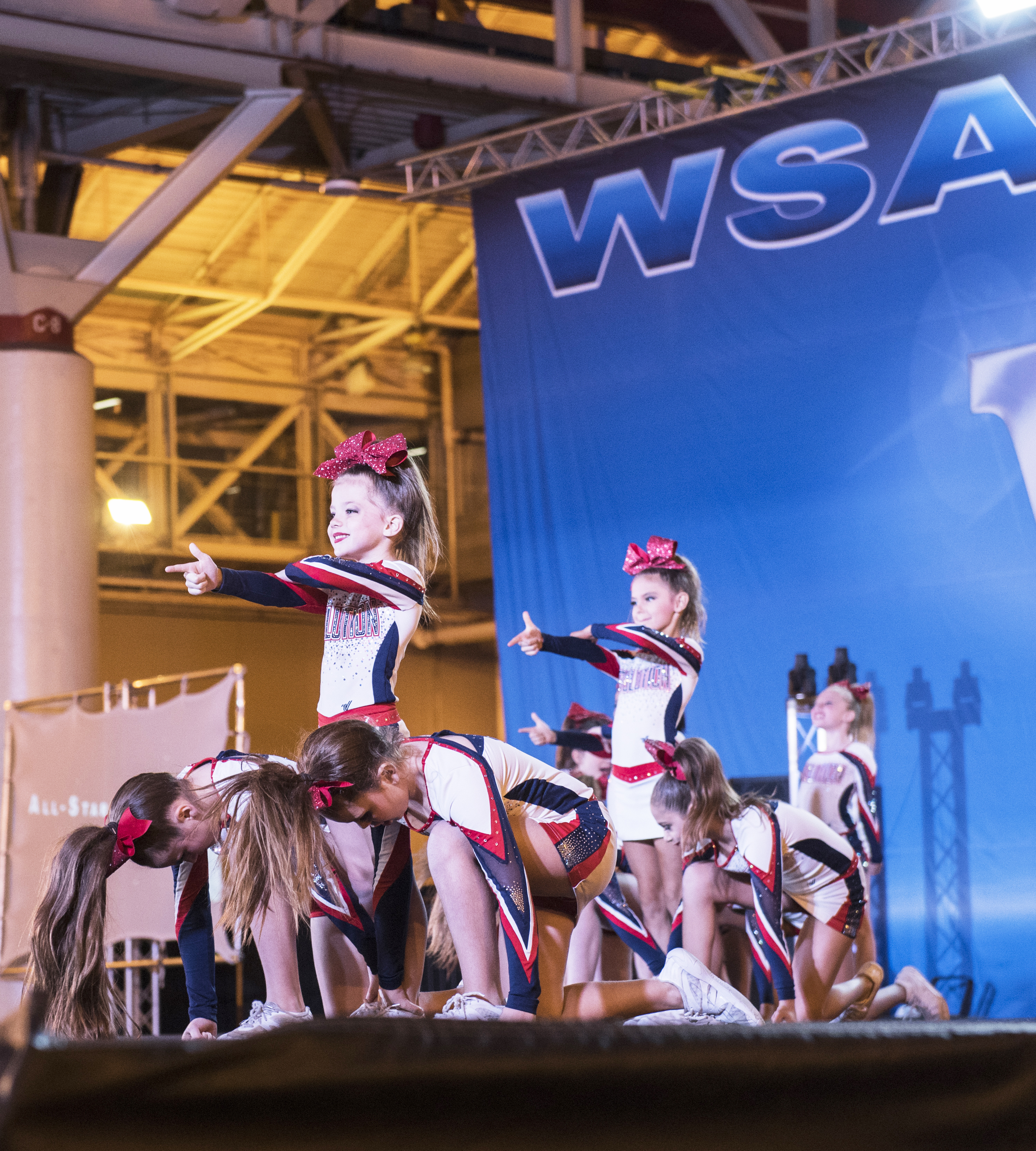

Electronic music blaring, lights flashing and heart pounding, Teri Meliet holds her breath as her daughter Katelyn flies through the air.

For two and half minutes, she’s on the edge of her seat following each carefully choreographed movement that will eventually return her 10-year-old safely to the mat.

“I trust them; you know how hard they work so you just want them to do well, but I’m holding my breath just hoping they succeed,” she says of her daughter’s all-star cheerleading team. “I truly never thought I would be that mom at a cheer competition. It is a different world for me, but I wouldn’t change it for the world.”

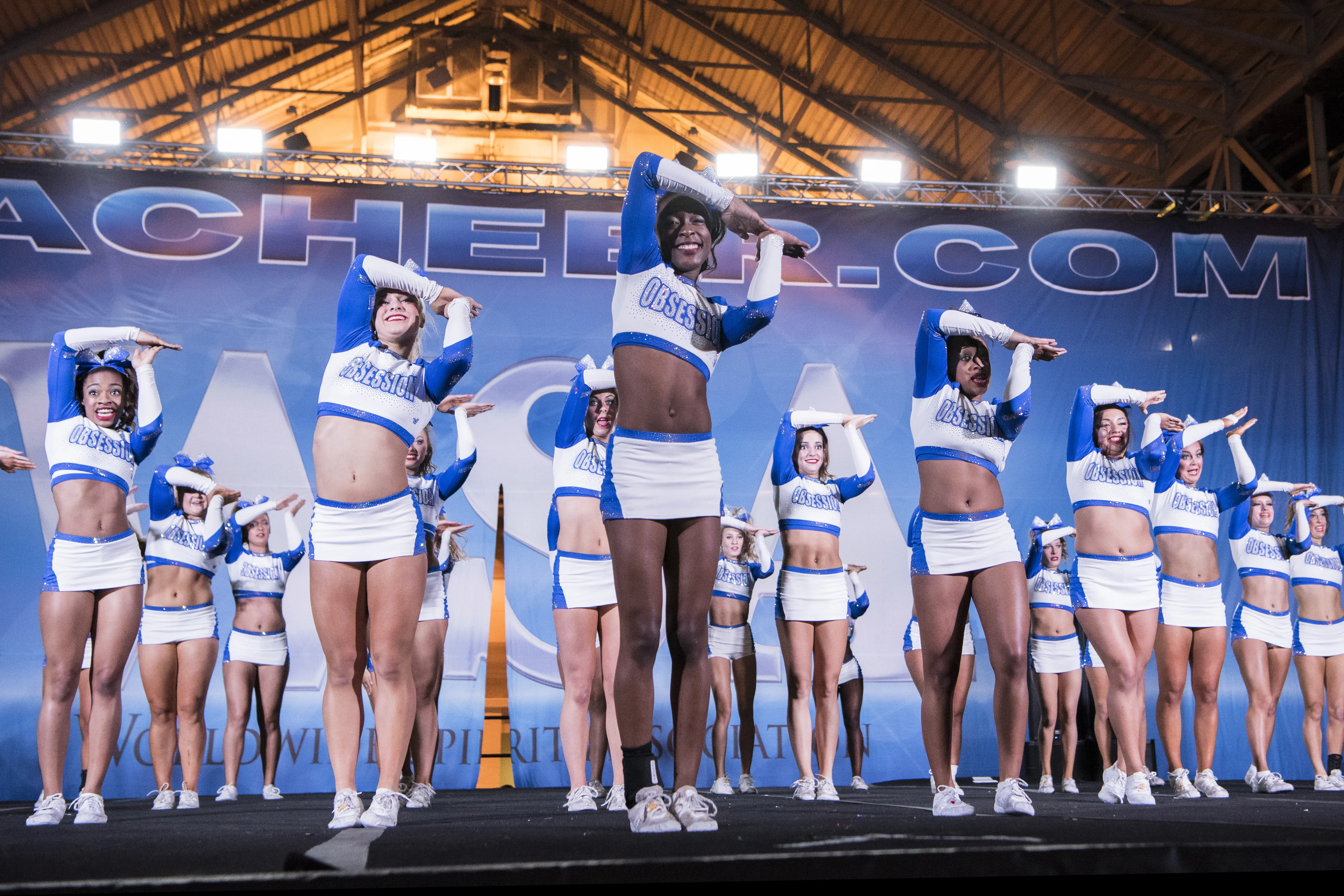

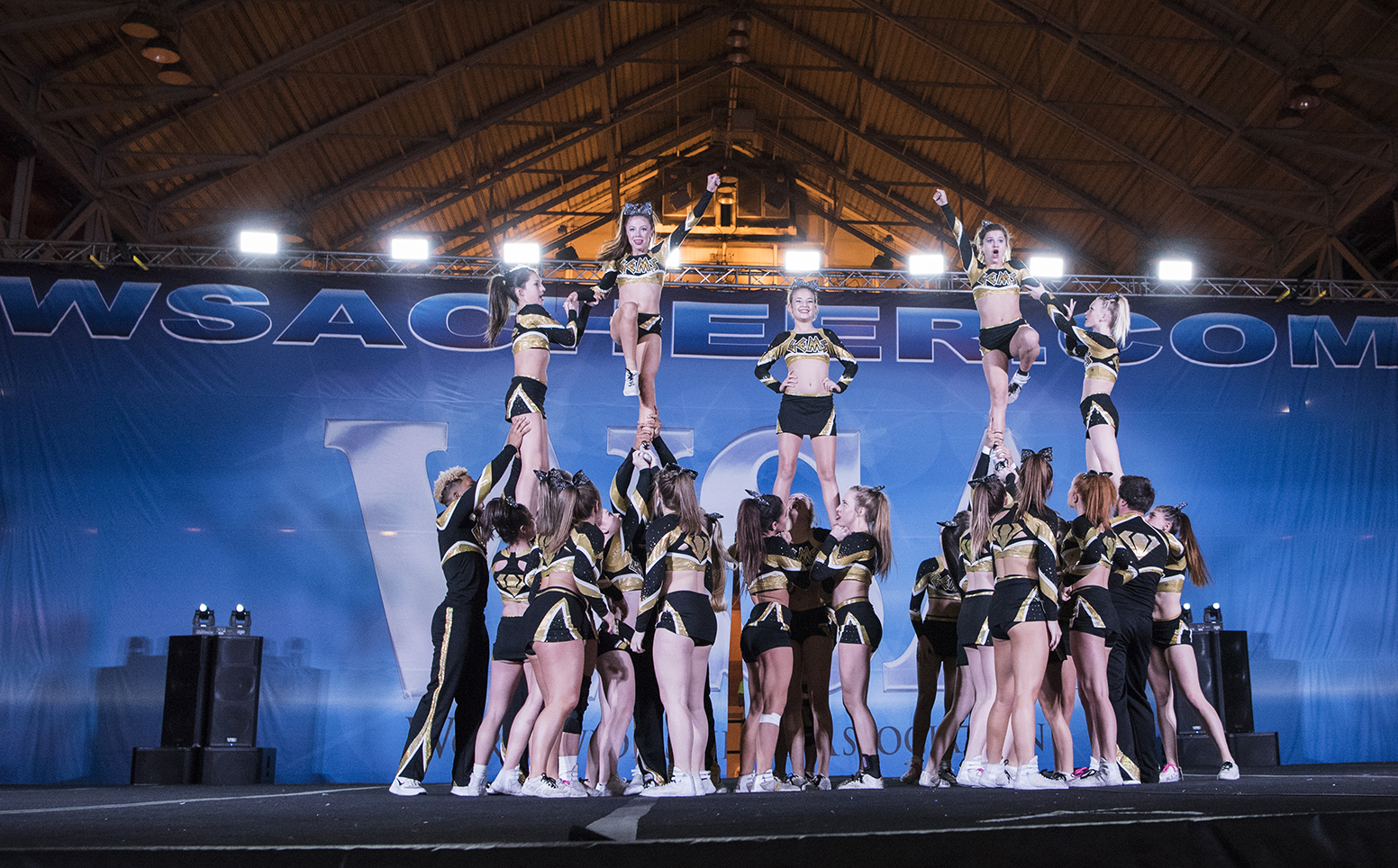

All-star cheer, also known as competitive cheerleading, is characterized by high-flying acrobatics, complicated lifts and coordinated tumbling, not the spirited synchronicity seen on the sidelines at school sporting events or the eye-candy entertainment popularized by the NFL, NBA and other professional sports in the United States.

Meliet’s daughter showed an interested in cheerleading at the age of two after Meliet took her to a mommy-and-me tumbling class. “There was no turning back after that,” she says. “It’s her passion.”

Eight years later, Meliet finds herself planning her family vacations around cheer competitions as her daughter competes on an all-star cheer team with Louisiana Cheer Force, a competitive cheer program in Baton Rouge owned by Meliet’s high school best friend, Rachael Pearson.

“These girls are truly athletes,” says Meliet.

So much so that competitive cheerleading is on its way to becoming an Olympic sport. In December, the International Olympic Committee granted competitive cheerleading provisional recognition—the first step on a very long path toward inclusion in the Summer Games. During the three-year provisional recognition period, cheerleading can petition to be fully included in the Summer Games.

Many see this as long overdue validation and legitimization of a sport that’s seen rapid growth in the past decade and is still evolving.

“Somehow, deep down, I knew everyone would see and catch on to what I love and why I am so passionate about all-star cheer,” says Pearson, who started cheering in the second grade and never stopped. As an LSU cheerleader, she began coaching competitive cheer and opened Louisiana Cheer Force in 2000.

In 1990, as a sixth-grader, Pearson cheered on one of the first of roughly a dozen all-star teams in the country. Cheer veterans Darren and Nicole DeMoss, who later left the coaching business to put on cheer competitions, owned the Baton Rouge program.

“We paid our way through college doing that,” says Darren. “Nicole and I cheered for LSU and coached on the side.”

Today, the all-star programs they once coached are now their clients. “Around 1999, we got out of the gym and summer camp side of the business and put all of our effort into expanding the competition side of the business.” Today, as the owners of the Worldwide Spirit Association (WSA), their competitions see over 23,000 students compete in more than 30 states.

The DeMosses say the rise in popularity of all-star cheer, which began in the early ’90s, can be attributed to the advent of formal, organized cheer competitions, like the full production events created by companies like WSA.

“It gave those kids a way to be rewarded for their efforts,” Darren says.

As Pearson explains, “Competitive cheer really gives you the ability to compete at your true level. I loved the social aspect of my middle and high school teams, but the competitive all-star cheer team was the true athletic sport that I had trained for my whole life.”

Like many team sports today, participating in a club or travel program in the off-season or even year round is key to securing a position on a school team and imperative for those athletes looking to make it at the collegiate level.

“If you ask a teenager, they are going to say, well, I want to make LSU cheerleaders,” Pearson says of her athletes.

Beyond the collegiate level, the pinnacle of achievement for all-star cheerleaders is the status and recognition that comes with winning competitions, according to Nicole.

And until competitive cheer makes it into the Olympics, the highest level of achievement is winning a title at the annual Cheerleading World Championship, also known as Worlds, in Orlando, Florida.

In 2014, Pearson’s senior, co-ed Level 5 team took home a bronze medal from Worlds, after competing against 90 teams. “I think we really put Louisiana on the map with competitive cheer,” she says.

While the Bayou State is not considered a cheer powerhouse, Darren DeMoss says Louisiana is “up and coming” in the cheer world when compared to dominating cheer states like Texas, Florida and California that have larger populations and therefore can pull from greater talent pools.

But Baton Rouge certainly has seen a surge in the sport’s popularity over the last five years.

Nicole says that might be because Baton Rouge is a big city that often acts like a small town. “A team can pop up and want to be competitive and what happens is everyone wants to be a part of it,” she says.

Additionally, as Darren explains, the barrier to entry is not very high for someone looking to start up a team. “In other words, if you want to start a competitive cheerleading program, you don’t really need a lot of money to get started as a business.”

And for young girls not interested in sports like softball, volleyball, basketball or gymnastics, competitive cheerleading opens a new door. “I think before this existed, the only thing similar to it for girls was competitive gymnastics,” Nicole recalls. “So if you wanted to be a competitor and an athlete, this gave a new opportunity to all those young girls to do that at a very successful and very high level.”

Another attraction: it won’t break the bank.

“If you put your child in any other activity at this level—the time commitment, the travel commitment, the competition commitment—it is probably going to cost you more than all-star cheer will cost you,” Darren says.

Additionally, companies like WSA help eliminate the costs associated with travel by bringing competitions closer to home.

“Once it had grown where everyone wanted to do it, you didn’t have to be, per se, ‘the rich’ to do cheerleading because companies like ours offer competitions at the local level,” Nicole explains. “So you don’t have to fly to Florida or Atlanta and stay in a hotel. You can compete right here in Baton Rouge.”

Now having been part of every facet of the sport—from being athletes themselves to putting on competitions to parenting four kids, two of whom are in all-star cheerleading—Nicole and Darren pride themselves in helping the sport grow locally by mentoring new coaches and focusing on increasing access to competitive cheer.

“We want to make cheerleading affordable and accessible to everyone who wants to do it,” Nicole says. “I do think that is why it continues to grow.”

As the DeMosses watch their daughters cheer, they hope their girls will come away with some of the same life lessons the sport instilled in them.

For Darren, the biggest takeaway from his cheer days was learning to be part of a team to accomplish a goal. “Working as a team resulted in a 21-year marriage with four kids and a business,” he says. “Cheerleading is really the ultimate team sport … everyone is dependent upon everyone else’s role and everyone’s role is overly important. You can’t just bring someone in off the bench like in other sports.”

Darren and Nicole both cite confidence as another priceless quality gained. Nicole watches these and other virtues develop in young cheer athletes today as she coaches her daughter’s school team.

“To get to see these young middle school girls, what cheerleading does for them—it’s incredible to watch them blossom from the beginning of the year to the end of the year,” she says. “They become like different people.”